The largest lecture hall in Ingraham Hall, where Adrienne Thunder MS’97 worked for 12 years with the UW’s Cross-College Advising Service (CCAS), seats 484 people. It’s enough to accommodate all of the remaining fluent speakers of the Hoocąk (Ho-Chunk) language — nearly 10 times over.

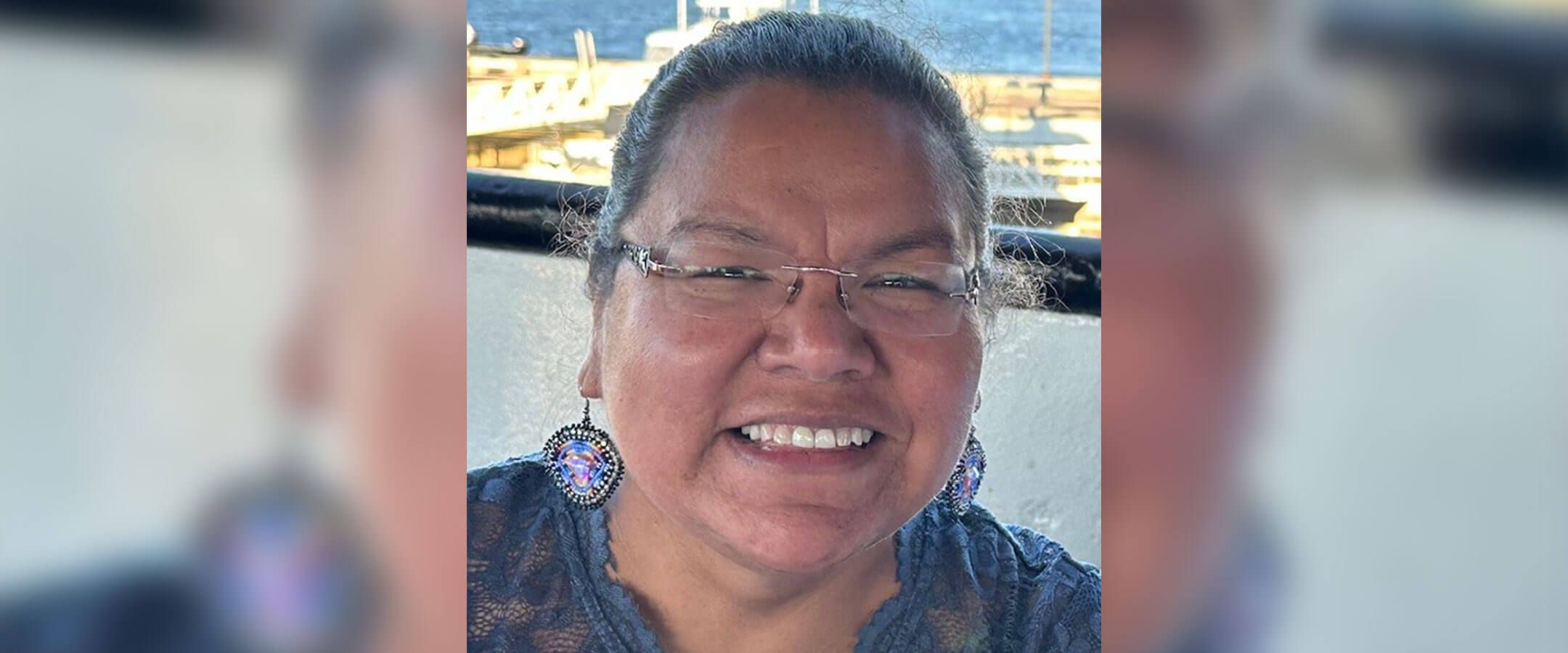

Now the manager of the Ho-Chunk Nation’s language division, Thunder is working to fill those empty seats with students seeking to preserve their ancestral tongue.

“We’re trying to encourage as much Hoocąk usage in every aspect of our lives as we can,” she says.

For Thunder — a language learner herself — the work of encouraging it in others merges her love of education with her dedication to serving her tribal community. After academic advising with CCAS, she returned to the Ho-Chunk Nation in 2011 as executive director of the Ho-Chunk Nation Department of Education under President Jon Greendeer. It was in this role that she began to recognize the potential for disentangling education from its fraught history in the Ho-Chunk community.

Years of violent cultural oppression in Wisconsin’s federal Indian boarding schools made tragic headway in the eradication of the Hoocąk language and also created lasting negative associations with educational institutions. By developing culturally relevant curricula that prioritize an Indigenous approach to education, Thunder and her team are reversing years of loss by giving new life to the language that, according to Ho-Chunk oral histories, first gave life to their people.

“[I was] thinking about education as nation-building,” Thunder says, referring to the concept developed by her friend and mentor Bryan Brayboy, a member of the Lumbee tribe and current dean of the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University, and other leading Native higher-education scholars. “[This looks like] Native people exercising our sovereignty and choosing the tools we will take up to continue building our lives and futures. Language has to be part of that.”

Today, the Hoocąk Academy — the teaching and learning arm of the Language Division — builds their nation by reaching students across generations. From Hoocąk-language childcare programs and educational resources for K–8 students to in-person and online courses for adult learners, the the Hoocak Academy endeavors to increase their endangered language’s longevity by making it accessible to every member of the Ho-Chunk community.

Their approach also extends into Wisconsin’s public education systems. The division works with high schools in Tomah, Wisconsin Dells, Black River Falls, Nekoosa, and Baraboo to implement Hoocąk-language courses and is partnering with the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse to offer a dual-credit Hoocąk-language course.

“We’re trying to hit all of the generations in whatever way is comfortable to them,” Thunder says. “Even if everybody is still novice level, and they’re practicing with one another with what they know, [they’re] keeping it alive so that the next generation doesn’t have as far to go when they start their language journey.”

Did you grow up around Hoocąk speakers?

My dad is fluent; he’s one of our eminent speakers. I grew up hearing the language, but like so many people of my generation, the language was spoken around us, and it was spoken in front of us, but it didn’t include us. … We did pick up some words hearing it all the time in different settings and around the home, but it wasn’t something that was conveyed to us. … I think that’s the legacy of boarding schools and all of the trauma that [our elders] went through, the punishments that they experienced because they used their language.

Did this history of boarding schools and language eradication in the Ho-Chunk Nation influence your own educational journey?

I had really supportive aunties who saw what I was able to do academically and really encouraged me to learn. And they were really invested in education. My grandmother had attended a boarding school, and that led to a really difficult relationship, not just in our family, but in lots of Ho-Chunk families where people attended either the Tomah Indian School, the Neillsville Indian School, or the Bethany [Indian Mission] in Wittenberg, Wisconsin. People of my grandparents’ generation and some of my parents’ generation were students from those Indian schools, and so we have a really complicated relationship with education. But they also understood that it was really important.

Your programs are intentional about incorporating tribal values. What are some of those values, and how do you infuse them into educational models?

Kinship is really important with our people: kinship in terms of bringing together community and maintaining connection as much as possible. … We really want to make sure that our young people understand that the relationships are not just to the people but to the land, and that everything that we hold dear, those relationships have to be kept strong. When you’re thinking about student development, you’re not just thinking about the psychosocial aspects of human development behavior; you’re also talking about your relationship with the environment and your relationship to spirituality.

In college, too, a lot of people tend to think about earnings and income and high-paying jobs and things like that. Those things are important in tribal communities, too, because you have to raise your children and take care of your elders. But you have to nuance the message a little bit so that [tribal] values are coming forward more than earning capacity all by itself. A lot of Indigenous people value generosity and being able to contribute to your community; being able to support your larger family, whether it’s your elders or grandchildren; and that you’re making enough so that everyone is taken care of.

Hoocąk is considered an endangered language. What do we stand to lose if the language is lost?

[Hoocąk] conveys our connection with one another. When we talk with one another, you have to know kinship and how you’re related to somebody, and the status is really important in whatever you’re conveying. [If] you’re talking to an elder or if you’re talking to a younger person, that’s going to be a little bit different. … The way our language conveys anything, really, you can practically see what’s happening. ... We have positionals in our language, so you could be able to tell whether the people [speaking or being spoken to] are standing up or sitting down or lying down or in motion. It’s a really visual, very active, dynamic language. You hear all the time that sometimes you can’t convey something in English from another language because there’s not enough nuance in English that can be found in other languages, and that’s probably true of Hoocąk, as well. There’s a lot that is lost in translation.

The Ho-Chunk people are also known as “the People of the Sacred Voice” or “the People of the Mother Tongue” because of their role in helping to shape the Siouan languages of the West and Midwest. How does this influence the imperative to preserve and revitalize the language?

There’s a lot of weight and importance behind language preservation and revitalization [already]. But the origin of our language, the fact that it was a gift to us from our creator, and that when he breathed life into us, the first thing to come from us was our voice, our language, and the very first thing that we did was to thank the creator for gifting us with this — it’s a way of us being able to not only thank him, but to be able to share this life experience with other human beings. It’s a sacred thing.

One of your division’s intentions is to expand the functionality of the Hoocąk language into everyday life and to “bring Ho-Chunk into the 21st century.” What does this look like in practice?

We wanted to develop a program where we are working on expanding the lexicon and working with the eminent speakers to develop words for things that we didn’t have words for. As we’re developing the information age and the computer age, there’s a whole lot of things there that we weren’t able to find words for, so we did a dictionary project. We were working with the Administration for Native Americans and the Language Conservancy, and they worked with us for the last four years, really, to develop not only the lexicon and to break down the domains that we needed to work on for developing more terms, but we also started working on the dictionary app, which we launched in 2022.

Are younger generations participating in these language revitalization efforts?

You’re seeing a lot more Indigenous representation out in the media, which is really nice, and I think that has fueled a little more interest in kids wanting to know more about their roots and wanting to know more about their language and what’s distinct about being Ho-Chunk compared to the other Indigenous identities they’re seeing out there. I think we’ve benefited from that, and I’m really happy to see our young people embrace it as much as they have.

At one point, our education coordinator, Jessi Falcon, had suggested that we use the youth along with the eminent speakers [when creating recordings for our app]. The eminent speakers did a lot of the introductory work, and then we decided to bring in the youth and they were doing some other recordings for the words, as well. Just watching that interaction between the youth and the elders, the eminent speakers — they were just so tickled to see the younger people using this and creating this resource for other people to learn language.

Learning a new language is no small task. How do you help introduce new students into the program?

[We can get caught up in] the history [of] getting our language separated from us and then us trying to bring it back together with the people. On one hand, we are trying to make it okay for people to not have that [linguistic] background, [because] there’s a lot of guilt and shame from people feeling like [they] should know this. [We’re] trying to make it okay that they don’t [while showing that] it doesn’t have to stay that way. We all have the power to be able to change that and to make that as positive and as welcoming and warm and joyful of an experience as we can.

The most recent class that we have developed is called It Starts with Me. We felt that a learner-readiness class was something that we really needed to do. So, part of it is to address that guilt and shame feeling, or whatever barriers might be in the way of someone [starting their learning journey], because a lot of this is self-talk as they’re going along and developing the confidence to be able to continue with their learning and taking the risk of making mistakes along the way. Then, we try to remove a lot of the mystery to Hoocąk language learning [by] telling them where the resources are [and] showing them what’s all out there and what the steps are in learning.

And the last product out of that class is their own language-learning plan. We’re not the ones telling them what they need to know or anything like that. We’re actually helping them think about what they would like to do with the language, and we’re going to be here to provide the guidance and support that will help them reach whatever those goals might be. We’re trying to establish them as the driver for language and not placing ourselves as any sort of authority, because we’re all learning. We’re all in this together.

How has this work been rewarding for you?

I thought going into the education area and working with our K–20 population — our older adults, even — on educational issues was really important. That was like, “Oh, good, I’m fulfilling my life’s purpose.” When I moved over to language, I think that was multiplied by a million. This area is just so central to who we are and how important that is to our people. I feel like there is no option for failure; we have to find a way.