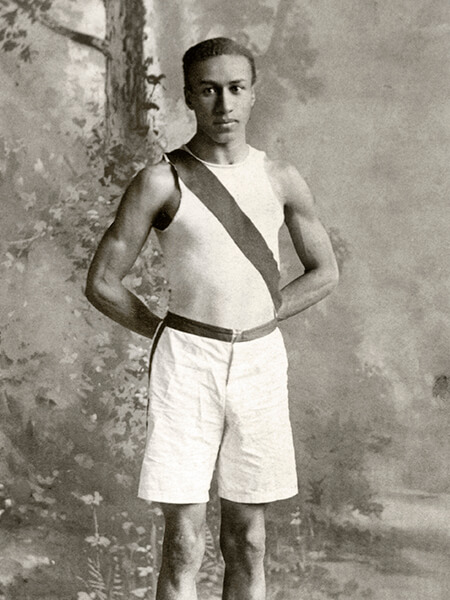

George Coleman Poage 1903, MAx1904 was a man of firsts, someone who approached challenges with determination rather than trepidation.

Poage’s family moved to La Crosse, Wisconsin, in 1884, when he was four years old. When his father died a few years later, the Poages moved into the home of Mary and Lucian Easton, his mother’s employers. The Eastons encouraged Poage’s education, and he fully embraced access to books in their home’s library.

Poage soon demonstrated superior academic and athletic skills. He was the best athlete at La Crosse High School, and he graduated second in his class, becoming the first African American to earn a diploma there. While working on a history degree at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he ran short sprints and hurdles for the varsity track team. His enrollment in graduate-level courses allowed him to continue to compete, and in 1904, he placed first in the 440-yard dash and the 220-yard hurdles, making him the first African American champion in Big Ten Conference track history.

The accomplishment caught the eye of Milwaukee Athletic Club members, and they sponsored him at the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis. The games faced a boycott over segregated facilities for spectators, but Poage decided to compete, earning bronze in the 200-meter and 400-meter hurdles and becoming the first African American to win Olympic medals.

Poage cleared hurdles on the track and in life.

But Poage’s star faded quickly during the Jim Crow era, when job opportunities were limited. He taught briefly at a segregated school, and then moved to Chicago, where he worked quietly as a postal clerk for almost 30 years. He died in 1962.

In 1913, a La Crosse newspaper had described Poage as “perhaps the greatest track athlete that was ever developed in this city.” The city honored his legacy by renaming a park in his honor in 2013 and unveiling a sculpture of Poage there in 2016.

Thank you, La Crosse County, for the record-breaking George Poage for inspiring others to keep their eyes on the finish line.