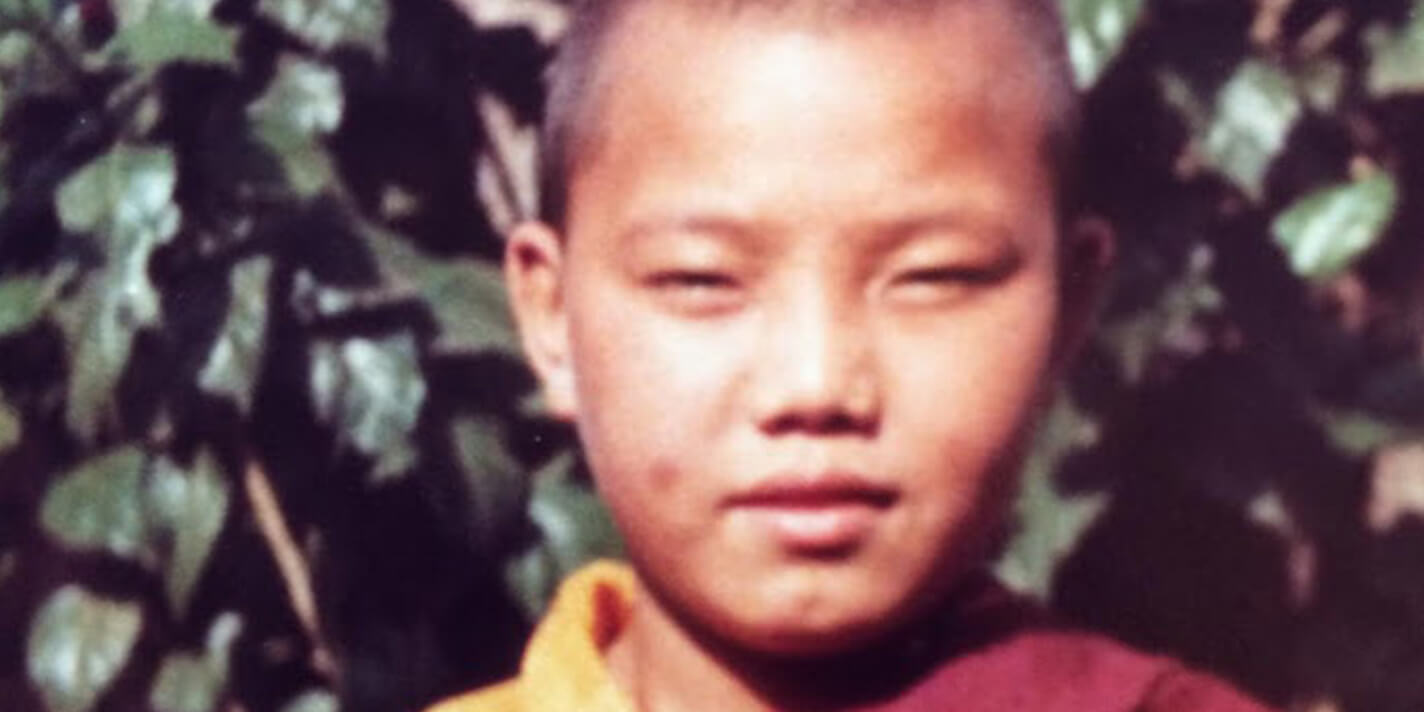

Jampa Khedup, a former Tibetan monk and a current lecturer at the UW, lives, breathes, and teaches Tibetan culture. But his story begins in southern India. That’s where his parents and 80,000 other Tibetans — along with the Dalai Lama — fled following a Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule in 1959. Khedup’s parents resettled in Mysore, India, and continued raising their family with Tibetan culture and language at the forefront.

Khedup’s parents chose him from among their five sons to pursue a monastic life. When he was 10 years old, Khedup left his family to live in a monastery and study Tibetan Buddhism. He spent 20 years as a monk, learning philosophy, memorizing scripture, and sharing in his order’s workload. By 1997, Khedup had completed his higher Buddhist studies and earned his Geshe degree — the Tibetan Buddhist academic degree for monks — from Sera Jey Monastic University in Mysore.

In 1998, Khedup came to Deer Park Buddhist Center in Oregon, Wisconsin, to assist Geshe Thabkay, Khedup’s personal spiritual adviser and a resident teacher at the center. Deer Park is the only Tibetan Buddhist Monastery in the state and located just a few miles from Madison. Khedup also worked closely with Geshe Lhundub Sopa, the founder of the Deer Park community, a highly respected Tibetan Buddhist leader, and a tenured professor of Buddhist studies in the Asian Languages and Cultures (ALC) department at the UW.

Geshe Sopa passed away in 2014, but as one of the first Tibetan scholars to teach in a Western university, his 30 years of service at the UW opened a door to educators with similar degrees and experiences. Khedup joined the ALC staff in 2005 to teach Tibetan language and culture courses, including Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism features heavily in the language and culture classes taught by Khedup. “Buddhism is embedded — the philosophy and lifestyle — everything is followed or practiced according to the Tibetan Buddhist philosophy,” Khedup says. He encourages his students to integrate some of the practices they discuss in class into their own lives, especially meditation. But he doesn’t believe one has to follow specifically Buddhist teachings to effectively meditate. As Khedup says, meditation can be done with the aim to improve immediate and long-term personal well-being. “Meditation can be understood in a very simplistic way, in a sense that you are adopting a new technique to overcome challenges. … That may be a simple breathing [exercise] like, ‘Take a deep breath in … just let it go.’ ”

Meditation is not the only feature of Buddhism that can promote personal and societal wellness. Love, compassion, and patience are highly valued in Buddhist philosophy, and each virtue benefits everyone when practiced. “The only way to peace and happiness is loving and being kind to others. There’s no other way,” Khedup explains. “The more selfish you are, the more frequently you really hurt. This is Buddhist practice, but then it’s [human nature], right?”

Khedup is no longer a monk — he’s now married with three children — but his love of Tibetan culture, practicing Buddhism, and preserving Tibetan identity is still central to his life. Every weekend, Khedup oversees classes for the Wisconsin Tibetan Association’s Wisconsin Tibetan Language and Culture School. This school aims to preserve the language and culture within the younger generations of Tibetan Americans. “All of the Tibetans in this community stay connected so that we can do a better job with preservation of the culture and language while we are in exile.” Classes start with the singing of the American and Tibetan national anthems before teachers like Khedup lead courses in Tibetan history, traditions, and music.

Working with the members of Deer Park Buddhist Center also helps Khedup maintain ties with the Tibetan community. In early March, Khedup participated in organizing Tibetan New Year, or Losar, celebrations for Madison-area Tibetans. The holiday lasts for three days and consists of community prayer, temple offerings, and neighborhood parties. Like many new year celebrations, Losar also presents an opportunity to lay aside grudges and start again with a clean slate. “On a new year, we greet everybody regardless of differences or arguments,” he says. “On the New Year Day, you have the opportunity to rebuild broken relationships.”

Khedup’s volunteer outreach work is not limited to the Tibetan community. He visits hospitals to pray with anyone who requests a Buddhist spiritual leader or to practice meditation with patients suffering from mental health issues. He also visits middle and high schools and area churches to share different meditation techniques, demonstrate traditional chanting, and promote interfaith dialogue.

Khedup will continue to help bring up the next generation of Tibetans in the Tibetan language — and anyone else who wishes to integrate Buddhist philosophy and meditation in their daily lives. After all, as Khedup explains, “Human beings all share the same struggles and have many similar ways of overcoming these challenges.”

Please contact Jampa Khedup for any inquiries about Tibetan language and culture courses at: Khedup@wisc.edu.