For his day job, Alexander Shashko ’94 is a UW–Madison lecturer, and a fairly popular one. He teaches Afro American Studies 156 Black Music and American Cultural History, which he took over from legendary professor Craig Werner, as well as AAS 154 Hip-Hop and Contemporary American Society, and AAS 272 Race and American Politics from the New Deal to the New Right. His classes are generally packed, and he’s won teaching awards, including the Honored Instructor award from University Housing. But equally intriguing is some of his work outside the classroom: Shashko is one of the voters for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

How did you first come to the UW?

I grew up in Shorewood, Wisconsin, so the UW was in my backyard. The combination of quality, affordability, and proximity made it pretty enticing. It wasn’t that complicated for me to make the decision, actually, even though I did have some other choices.

Who were your influences when you were an undergrad?

My focus was really on American history and politics, so I had a bunch of great classes. In history, I got to study with Bill Cronon, Paul Boyer, and John Cooper, in American history, and David McDonald in Russian history. I had several, terrific [integrated liberal studies] professors, too, like Mike Hinden, Bob March, and Dan Siegel. Those are just some of the names that immediately come to mind.

How did you get from history and political science to music?

My music education ran separately from my academic education. As an undergrad, I definitely had an interest in music and studied about cultural theory and the history of popular culture. But I didn’t directly study the history of music. That was a personal voyage, one that started when I was a kid with a little transistor radio hidden under my pillow so I could listen to music when it was bedtime. I would stay up late and listen to everything from current pop music to the oldies. My mom was a big fan of the music of the late ’50s and early ’60s, so there was a lot of the Beatles and Chuck Berry and Little Richard and Buddy Holly and Elvis.

But it wasn’t part of your college education?

I did a little bit of reviewing for the Daily Cardinal when I was an undergrad. I just dabbled in it. I was a semi-host at the college radio station. I didn’t have a formal role, but I would show up more often than not to do radio bits with my friends who did have shows. And so, my interest in that was always pretty strong throughout my undergrad years.

You took over Craig Werner’s legendary course. How has it changed during your years?

What I have done is extend it chronologically because every year there is a new batch of music that you have to add to the story. I probably cover double the amount of material that he did in the same period of time. It is also a very different class because students have easy access to music now. I can mention almost any song, and they can find it if they don’t know it.

Do you include current artists?

Oh yeah, I go all the way to the present. I don’t spend as much time in the present as I would like to, but I’m always resisting my historian’s sensibility for staying in the past — which, of course, I want to honor because one of the central ideas of the class is that you’ll understand the music of the present if you better understand the music of the past.

Who are today’s most influential artists?

Well, that’s always a difficult question. Sometimes I look back and say, “Well, we thought this person was going to be giant and they weren’t.” But you have to talk about Beyoncé and the role that she has played as a cultural and musical figure in terms of being a voice for Black women. There are a number of African American hip-hop artists right now, like Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion, and a lot of their success goes back to Nicki Minaj and the role that she plays in really becoming a female hip-hop superstar. Kendrick Lamar — who has not put out an album for a few years now — I think his presence hovers over everyone in the hip-hop community in terms of the sheer breadth of his skill and his commitment to using his music both to have fun and to create a platform for talking about more serious issues. Those are a few of the names that come to mind off the top of my head.

How did you come to the attention of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Several years ago, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame decided that they wanted to expand the number of voters for the Hall. They started to look around for people who they felt were qualified and interested. They asked people who were already voters, people who were already in the world of music history and music criticism, and my name came up, and they sent me an invitation. I wish I had more details about that.

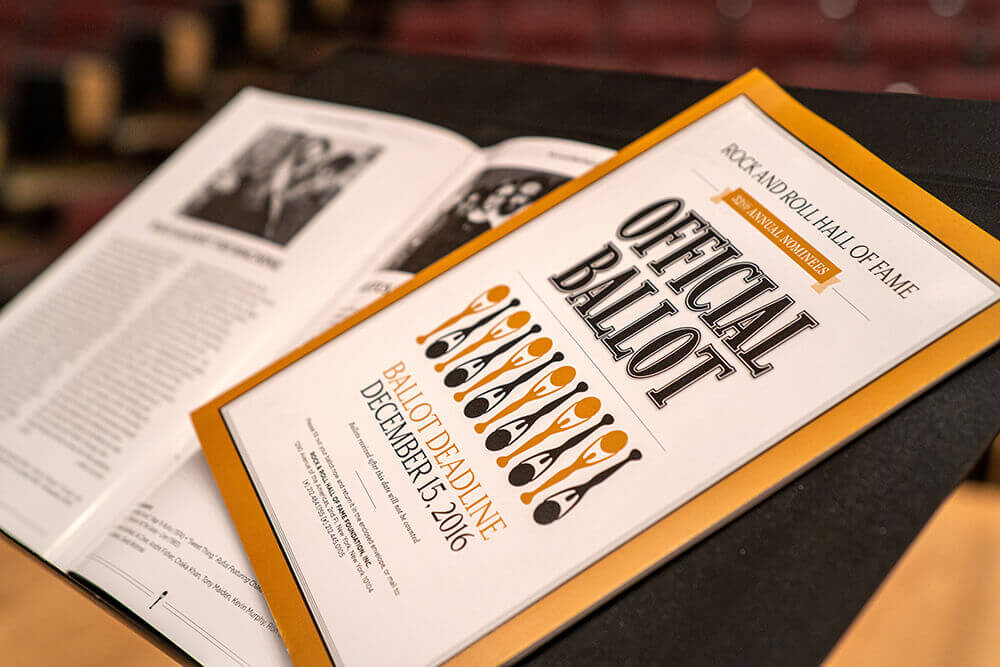

How does the voting process work?

The committee meets, usually in the spring, and they make decisions about who is going to be on the ballot. They’re paying attention to what people are talking about in the public in terms of who is worthy and who is not, about new information about artists over time. They create a ballot that has descriptions and a short essay on each of the nominees. We check off the names, and we send it in, and that really is the entire process.

Sounds simple.

You can spend as much or as little time on it as you want to. I do know that a lot of music writers, music critics, and music historians — we tend to take it very seriously. I’ll go back and listen to the music of the nominees, and I’ll read some of the best books and essays that have been written about them. In the YouTube era, you can go back and watch performances. I know some of the voters, and so we’ll talk about what they’re thinking about and why. Then you make a decision based on who you think are the worthy but also sometimes who has the best chances of winning. There is a strategic element to the voting because, from my perspective most of the artists on the ballot are worthy of induction but you know that they’re not all going to make it. Ultimately, no more than 20 percent of your choices end up being the ones that get in.

How does the ballot work?

The number of artists does vary slightly, but it’s usually somewhere around 15 to 20. I want to say closer to 15. You choose five. We do not have ranked choice; you just pick the five, and they tally the votes. It’s a straightforward process that way.