To understand the late, trailblazing UW kinesiology professor Betty Roberts MS’50, PhD’60, a good place to start is on a refrigerator ship crossing the Atlantic Ocean in 1945.

The ship cut a path through German U-boat-infested waters to deliver volunteers to the British Army. Among them was Roberts, a recent college graduate from Canada. She traveled alone, accompanied only by her conviction, a level head, and quite a bit of courage.

“She was distinctly different from practically every other person I knew,” says Tom Roberts, Betty’s husband of 12 years and longtime friend. “She had this curiosity and the courage to take on projects

nobody else would.”

In her career as a scientist, Roberts often reflected the courage and independence she showed on

that ship.

From 1949 to 1989, her research in UW–Madison’s Department of Physical Education for Women was groundbreaking and game changing — literally. Roberts’s studies on how athletes’ bodies work altered forever how scientists, coaches, and players understand and approach things like shooting a basketball, kicking a field goal in football, and taking a slap shot in hockey.

“She had an inquisitive mind; she had a creative mind; she had a brilliant mind,” says Ron Zernicke MS’72, PhD’74, one of Roberts’s students who went on to serve as dean of the University of Michigan’s School of Kinesiology. “She was an inspiration.”

Intelligence and Optimism

At eight years old, in a rural Canadian lake, Betty Roberts learned to swim.

As her mother shouted instructions from the shore, Roberts worked out the mechanics of the breaststroke. Years later, as a student at the University of Toronto, she would be crowned the 1939 intercollegiate breaststroke champion.

A lifelong passion for sports was one of Roberts’s defining traits, and that passion led to her professional calling.

After her service in World War II — she drove trucks for the British Army, turning down roles as a cook or typist — Roberts and a dancer friend set out to find graduate programs in physical education. Two options presented themselves: Columbia University in New York and the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

“We didn’t know where [Wisconsin] was,” Roberts admitted in a 2010 interview with UW–Madison’s Oral History Program. “We came here because of dance, and because we were accepted, and because we couldn’t afford New York.”

Roberts enrolled in 1949, a golden age for physical education at the UW when scholars like biomechanics trailblazer and physical education professor Ruth Glassow 1916 and dance professor Margaret H’Doubler 1910, MA1924 were at the leading edge of science, art, and the intersection

of the two.

Glassow focused on filming athletes in action, breaking down their movements frame-by-frame. H’Doubler established the nation’s first dance program, presenting unconventional ideas about how dancers could move. Roberts combined the insights of her role models in her master’s thesis, which focused on the optimum speed and angle for basketball shots. She discovered that shots with a flatter

arc than was considered “best practice” were more likely to make it in the basket.

As Roberts recalled in her Oral History Program interview, H’Doubler was also keenly interested in the science underpinning the art of movement.

“Margie H’Doubler was always talking about the nervous system,” Roberts said. “We were always talking about kinesthesia and how movement feels, but also what’s the underlying mechanism for this, and what does it have to do with movement execution? So that’s what got me.”

H’Doubler’s emphasis on the nervous system led Roberts to focus even more intensely on “anything

we could find out about the nerve.” In 1960, she earned her doctorate with a dissertation that studied how gamma motor neurons control muscle spindles, skeletal muscles’ stretch receptors.

At the time, the research on such tiny mechanisms was considered practically impossible.

“It was an unlikely project. It was the kind of research project nobody in the area of physical education

would be likely to carry on,” Tom says. “She just had the curiosity and the bravery to take on a project like that. And the optimism.”

Making Headlines — and History

In 1965, Roberts, then a professor at the UW, married Tom — whom she first met as a fellow scientist on her muscle spindle project — and soon welcomed a son, Charlie ’88. Charlie remembers being raised in a house that buzzed on the frequencies of both sports and science.

“I knew both of my parents were scientists and were really passionate,” he says. “I remember them talking about how somebody can accelerate a baseball to 90-plus miles per hour, and how gamma motor neurons played an important role.”

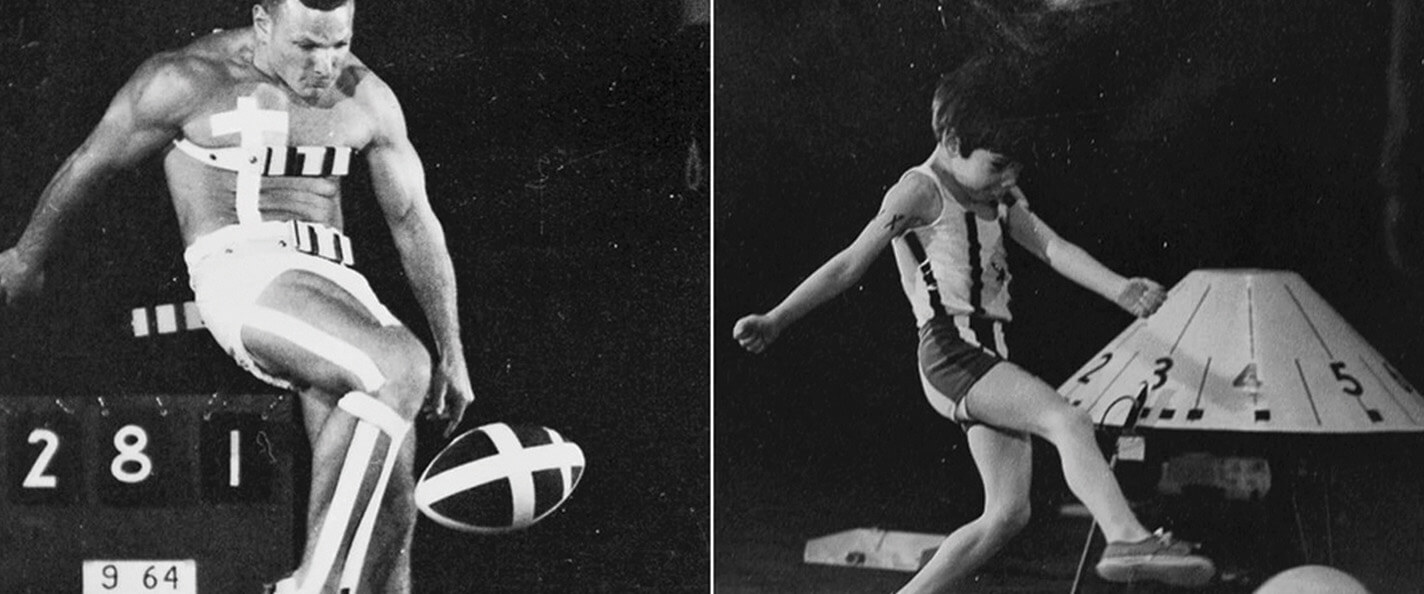

When Charlie was a toddler, one of his mother’s research projects upended conventional wisdom about how best to kick field goals in football (above). The project was inspired by one of Roberts’s graduate students, who wanted to know whether a “soccer style” field goal kick could be more effective than a head-on kick.

Up to that point, football kickers approached the ball straight on, while soccer kickers came at the ball from the side. Roberts’s research demonstrated the “soccer style” kick yielded both increased speed and accuracy.

Headlines on the project popped up across the country, including a 1966 Milwaukee Journal piece: “Professor Goes to Football Game for Kicks.”

The article explained Roberts’s scientific interests and qualifications but also said the whole endeavor “might seem like an unusual interest for a woman.”

Tom recalls Roberts being “amused” by the publicity.

“I think we both underestimated the impact that some of our work was having at the time,” Tom says. “That was a problem for both of us — we were not self-promoters. We enjoyed the work, got a kick out of the work. What else do you need?”

In a 2014 interview with the Canadian newspaper National Post, Roberts recalled getting letters about the study from some football coaches but “mostly from high school football players who wanted to become the kicker.”

“It generally takes a while for new ideas to get out, to catch on,” she said.

Today, thanks to her findings, every kick in football is approached from several steps to the side.

Several years later, Roberts recruited UW hockey star and future Olympian Mark Johnson ’94 to help her study the slap shot (right). Using tiny gauges (designed by Tom) affixed to both Johnson and to his hockey stick, Roberts took measurements and frame-by-frame shots of how Johnson executed the shot.

Charlie, then a middle schooler, was thrilled to be pulled out of class to be the control participant in the experiment, skating and shooting alongside the future 1980 Winter Olympics “Miracle on Ice” player. Together, the group discovered that hockey sticks made contact with the ice before the slap shot, causing the shaft to bend. The stick then sprung back and accelerated the puck to high speed. Realizing the stick functioned as a spring led to improved manufacturing, enabling players to better amplify the force and efficacy of their motion.

“My mom and dad were so excited by these discoveries,” Charlie says. “It led to many hours of conversation in our household.”

Supporting the Next Generation of Sports Scholars

Roberts went swimming on her 103rd birthday in April 2023. Local news got wind of her plan, which earned her another set of headlines. As usual, the headlines left her amused but unfazed. She just wanted to swim.

Nine months later, Roberts passed away peacefully just one week after her last spin on the bicycle ergometer.

Roberts’s passion for science lasted her entire life. In her final years, she read journal articles about molecular biology, following her son Charlie’s research. Charlie, raised on scientific inquiry, is now the director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

In 2021, Charlie created the Elizabeth M. Roberts PhD Academic Scholarship in Kinesiology Fund. Since its inception, the fund has supported three doctoral students in the School of Education’s Department of Kinesiology. The latest recipient, Emily Srygler ’17, PhDx’26 is studying youth sport participation patterns and sport specialization.

Charlie says supporting the scholarship of young people passionate about science is a legacy befitting his mother, who loved asking questions and seeking answers, uncovering hundreds of small truths about our bodies and some of our favorite pastimes.

“What do you get a 100-plus-year-old science nut who doesn’t care about having the niceties of life? Funding a UW scholarship in her honor was the perfect birthday gift,” he says. “Her curiosity drove her, and she got to be curious about the work of a new generation of students.”