UW professor and artist Tim Portlock was formally trained in media that he now calls analog. “Even though I really liked painting and drawing,” he says, “[the artforms] always seemed out of sync with the time that I lived in.”

In the late ’90s, when the adoption of the internet became widespread, Portlock was attracted to the new capabilities that computers offered. “With computers, you get what’s called nonlinear storytelling, where there’s more ability for the user or viewer to contribute to what’s happening and possibly changing the story,” Portlock explains. “I was like ‘Oh, this is new and exciting, and if I am doing this, I’m contributing to a brand-new language.’ ”

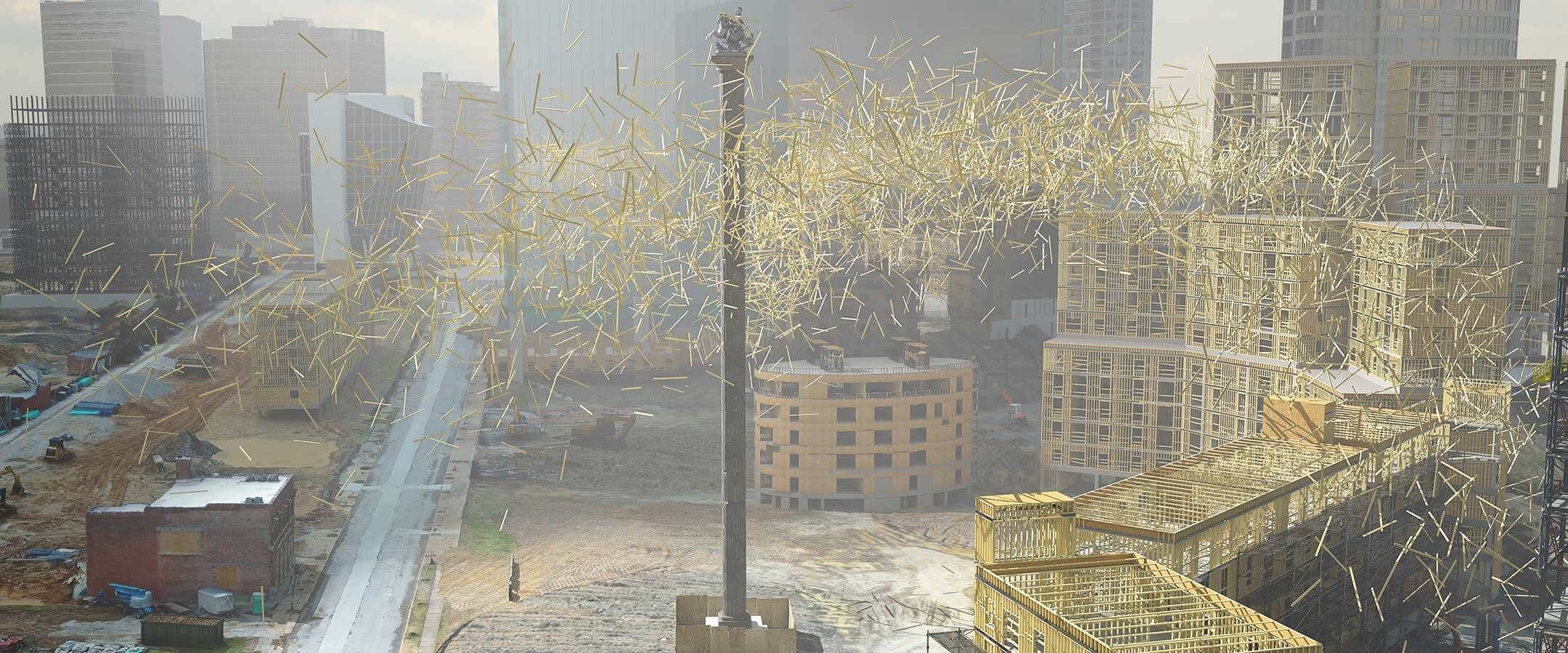

Portlock did, in fact, do “this” — two decades ago, he made the transition to digital artforms, including 3-D simulation and gaming technology. But he’s still influenced by and drawn to his roots in more traditional media. Landscapes, in particular, continue to be a focus of his work.

“The idea of landscape as an image and as an actual physical place is imbued with a lot of meaning,” he says. “As a digital artist, I’m still thinking about the meanings imbued in the image of the landscape and the place of the landscape.”

During the financial crisis of 2008, for example, Portlock’s work centered on the collective panic people felt over dying cities and nature reimposing itself. His digitally rendered works portrayed the wilderness reclaiming urban spaces and abandoned homes. Since the fall 2023 semester, Portlock has held a joint appointment with the School of Education’s Art Department and the Nelson Institute, where he’s continued to explore the meaning of natural and urban landscapes in a fast-paced world and changing environment.

His work with cityscapes often delves into national identity, such as the portrayal of American exceptionalism in 19th-century landscape pieces; health and financial crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic; and the juxtaposition of nature in urban spaces. Lately, Portlock has also been interested in applying speculative fiction and alternative historical fiction to his simulations, sharing a virtual look at his vision for the future.

With some of his creations, that vision can look a bit jarring, even dystopian. But every crumbling building, radiant sunset, and overgrown rooftop garden is composed with a bigger picture in mind: a call to action to stop and think about the world around us.

“I’m really into the idea of art activating people to want to do something or make a change or to think more critically about things,” he says.

Which leads Portlock to other benefits of digital: reproduction and distribution. Analog — paintings and drawings — are one of a kind. Originals are hard to come by and can be damaged. “With digital,” Portlock says, “it’s unlimited copies. … I can put something on a phone and some farmer in rural Africa can see it. That’s not possible with painting.”

With digital art, Portlock appreciates his ability to break new artistic ground all around the world, extending an opportunity and an invitation to explore visions of Earth’s future with everyone.