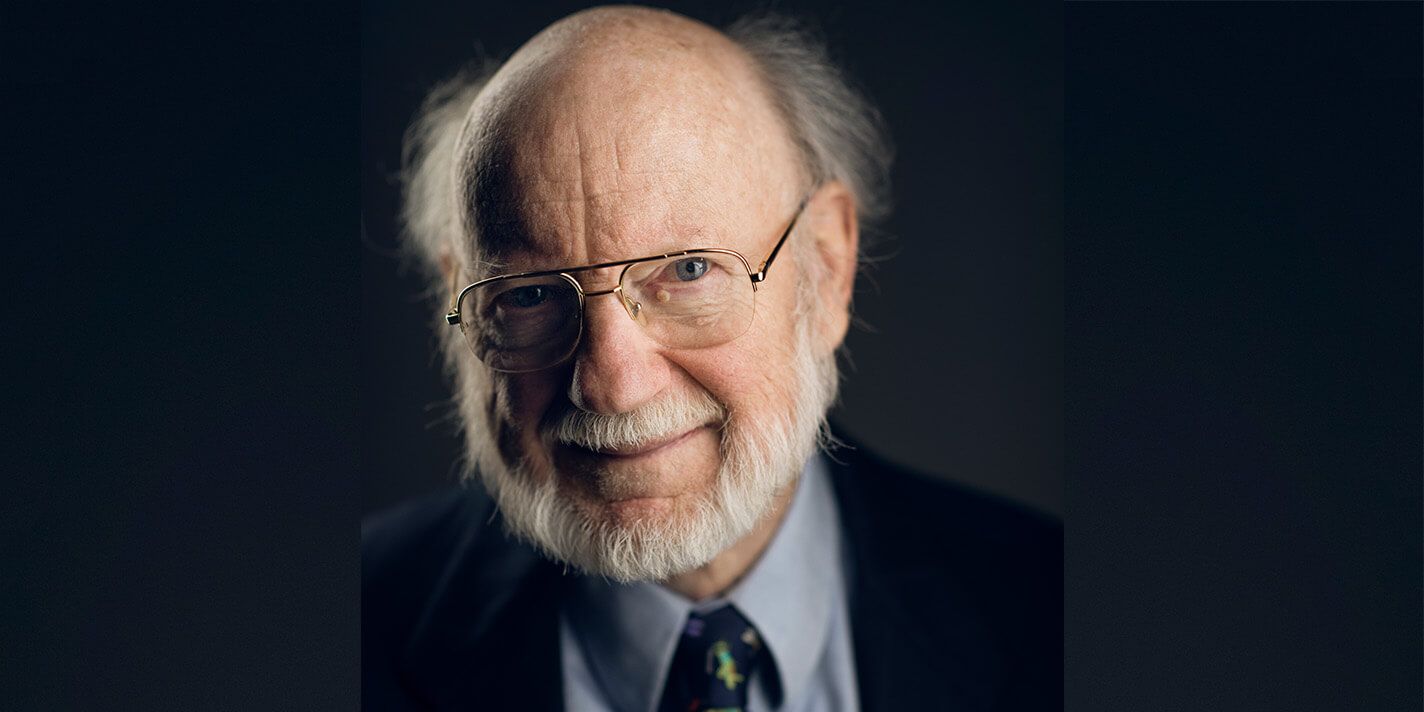

UW Major: Veterinary Science

Merck Research Scientist, Nobel Laureate

William Campbell’s path to a Nobel Prize started with a fluke — specifically, a sheep liver fluke. During a school trip to an agricultural show in rural Northern Ireland when he was 14, Campbell happened to read a pamphlet advertising a new drug for treating livestock infected with a parasitic flatworm commonly called a fluke. He remembers thinking how remarkable it was that one small pill could make such a difference for animal health.

A few years later, Campbell was a promising biology student at Trinity College in Dublin with a dual interest in veterinary and human medicine. His undergraduate adviser happened to be in touch with veterinary science professor Arlie Todd at UW–Madison, who was looking for talented graduate students just as Campbell was in search of a postgraduation direction.

Supported by a Fulbright travel grant, Campbell set sail on the Britannic in January 1953. In Madison, he moved into the Knapp House, which brought together graduate students from various disciplines to live in the former governor’s mansion near Lake Mendota. In the lab, he worked closely with both Todd and zoology professor Chester Herrick to study giant liver flukes in sheep and deer. Todd then coaxed a reluctant Campbell to consider applying his skills in the pharmaceutical industry. With some misgivings, he accepted a job at Merck and moved to Rahway, New Jersey.

“I only wanted to work on science for the sake of science and not for utility, but [at Merck] I discovered the tremendous joy and excitement of doing something that might actually be useful,” Campbell says. He stayed with the company for 33 years.

Campbell was an unusual industry scientist for his time. In addition to his assigned work, he regularly pursued independent projects that led to journal publications, invitations to academic conferences, and a fellowship in South and Central America usually reserved for university-affiliated scientists. One of those independent projects led to the discovery of a method to cryogenically freeze certain types of worms for as long as 10 years without killing them.

In 1975, Campbell joined a team working on cattle roundworms. That team eventually developed ivermectin, widely considered a wonder drug of modern veterinary science. In addition to treating cattle and horses, ivermectin was also the first convenient and widely used treatment to prevent heartworm in dogs.

Campbell’s interdisciplinary background helped him hypothesize another use for ivermectin: as a treatment for onchocerciasis, or river blindness. Caused by a parasitic worm and spread by blackflies, river disease was the second-leading cause of blindness worldwide before the 1980s. “I was in a position to propose that there were reasons why [ivermectin] might work in river blindness, and I passed that word up the line,” Campbell says. Clinical investigators proved his hunch correct, and Merck executives made the unusual decision to make the drug available to all who needed it for the prevention of river blindness. This, together with the dedicated work of several nongovernmental organizations, resulted in the eradication of the disease in many of the affected countries in South America and Africa.

The significant, ongoing impact of ivermectin led to Campbell sharing a Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015. He was invited to the White House to meet President Barack Obama, who gave Campbell a small stuffed toy in the shape of a heartworm.

Since retiring from Merck, Campbell has kept busy as a university lecturer at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey. He is also an avid painter, mostly of parasitic worms, and he regularly donates artworks to the American Society of Parasitologists to auction off as fundraisers for student scholarships.

“I like parasites, even though I’ve spent most of my life trying to kill them,” he says. “I often compare them to flowers — there’s an almost endless variety in their structure and life cycle. It’s absolutely phenomenal.”