A conversation with Professor Emerita Freida High Wasikhongo Tesfagiorgis MFA’71 about her career can feel like a conversation about everyone but her. Details of her own achievements are peppered across a canvas otherwise comprising colleagues, mentors, friends — sometimes all one in the same — and students, their names falling into the dialogue like splatters of paint from a brush. High’s legacy, however, is one worthy of solo exhibition: she rode the revolutionary momentum of the 1960s and advocated for change when her attempts at sharing and elevating Black art and culture were thwarted by institutional obstacles. Thanks in part to High, students at the UW have a department dedicated to the exploration and celebration of African American studies. They don’t have to venture far off campus to find exhibitions from Black artists. High’s influence is ubiquitous and reverberates as far as Black art and culture exist throughout the state, country, and world — though her roots remain firmly planted and lovingly tended in the Midwest.

High’s history as a trailblazing cultural activist has humble beginnings. Her educational journey started at a small religious school in Iowa. The conservative campus was a friendly environment, but not one suited to the protesting and organizing that was simmering on other college campuses in the heat of the civil rights movement and the burgeoning Black power movement. She transferred to Northern Illinois University, where the campus climate was no more welcoming to Black students than others of its time. Here, in addition to continuing to immerse herself in artistic practice and studies, she made her first foray into organizing by helping to establish the African and African-American Cultural Organization. With this group, she attended political events in nearby Chicago and cultural activities at the Afro-Arts Theater, a common meeting place for Black power activists.

High’s activism didn’t stop at the threshold of the lecture hall. In fact, it was these spaces that fueled her imperative for change. When an art history professor said that his course would not be covering Black artists because “there are none,” High turned her bewilderment to action: she began carving out space for Black artists in historically exclusive academia through independent study. (High subsequently completed an independent study on African American art with the very same professor.)

She brought her dedication to comprehensive cultural education to her first teaching job on the south side of Chicago, then to the Neighborhood Youth Corps in Rockford, and eventually to her graduate studies in art history at the University of Wisconsin.

“When I went into the art department, I also talked to the chair about my interest in studying African and African American art history on an independent level,” High says. “That small revolution of making a way to study that occurred at Northern Illinois came into the University of Wisconsin with me.”

Outside of her studies, movements sprung up across the country, many of them germinating in the fertile ground of college campuses. As antiwar, women’s rights, civil rights, Black power, and other agendas inspired demonstration and protest, High finally found herself on a campus conducive to joining the charge, a call she readily answered: not only through marching, but also through institutional change.

“There was the individual search for not only understanding the politics of the time, but also one’s place within that. My place within that was as a cultural activist,” High says. Although she arrived at the UW just months after the Black Student Strike of 1969, she enacted her own form of activism by joining the steering committee that carried out the first of the strike’s 13 demands: the establishment of what would become the Department of Afro-American Studies.

“What stimulated me to become involved with the steering committee was largely related to my interest in changing the dynamics of the campus and making it possible for Black students, white students, all students to have access to knowledge that our generation was denied,” High says. “My desire was to change the institution. How do you change the institution? You change the institutions by instituting new bodies of knowledge.”

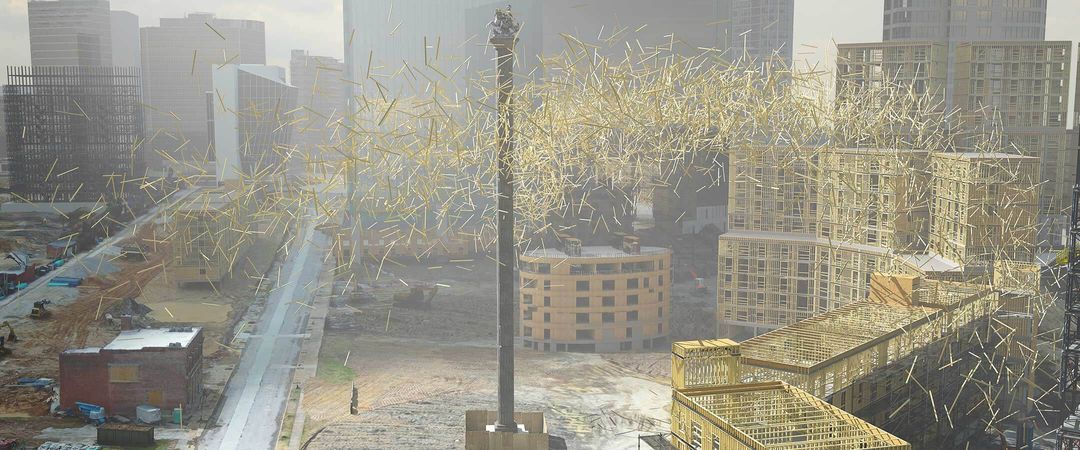

High was one of two graduate students elected to the steering committee. In addition to championing art history as a tenet of the department, High made an indelible artistic mark: she designed the department’s iconography, a mask motif that adorns the department's signage to this day.

After completing her MFA, High was asked to return as an artist-in-residence to the department that she had helped to establish. Her intellectual activism lived on through the opportunities and exposure she offered her students to art that the UW had yet to house. She invited artists like Faith Ringgold, Richard Hunt, and Benny Andrews to lecture in her classes. She took students on field trips to museums and exhibitions featuring Black art. She herself curated the first exhibition of African art on the UW campus.

“It was a part of a process of learning as we are breaking new ground and entering into the realm of academia,” High says of teaching in the young department. With the learning process of teaching came the unique challenges of being a department that was built from the bottom up, by students and per the demands of students.

“We’re born of struggle, and being born of struggle means that you are going to be very conscious of struggle in everything that you’re doing. Just because you are a department doesn’t mean that you are beyond struggle,” High says. “[The Department of] African American Studies had to legitimate itself because there were people who did not want African American studies, who didn’t believe that there was a need for African American studies.”

After becoming an assistant and, later, associate professor of art history within the department, High served three years as chair, leading the space that she had nurtured since its nascence in 1970 and seeing through the visions of the students that had demanded its existence.

“One of the main things that we were concerned with developing at the very beginning was that Afro-American studies was not to be an exclusive department in an ivory tower or an ebony tower. It had to have a community element,” High says.

“It’s intellectual activism, cultural activism, and that builds from the center of your own interests to the community. … I don’t think our work has ever been simply knowledge for the sake of knowledge. It has been knowledge with purpose, and that purpose had humanitarian values.”

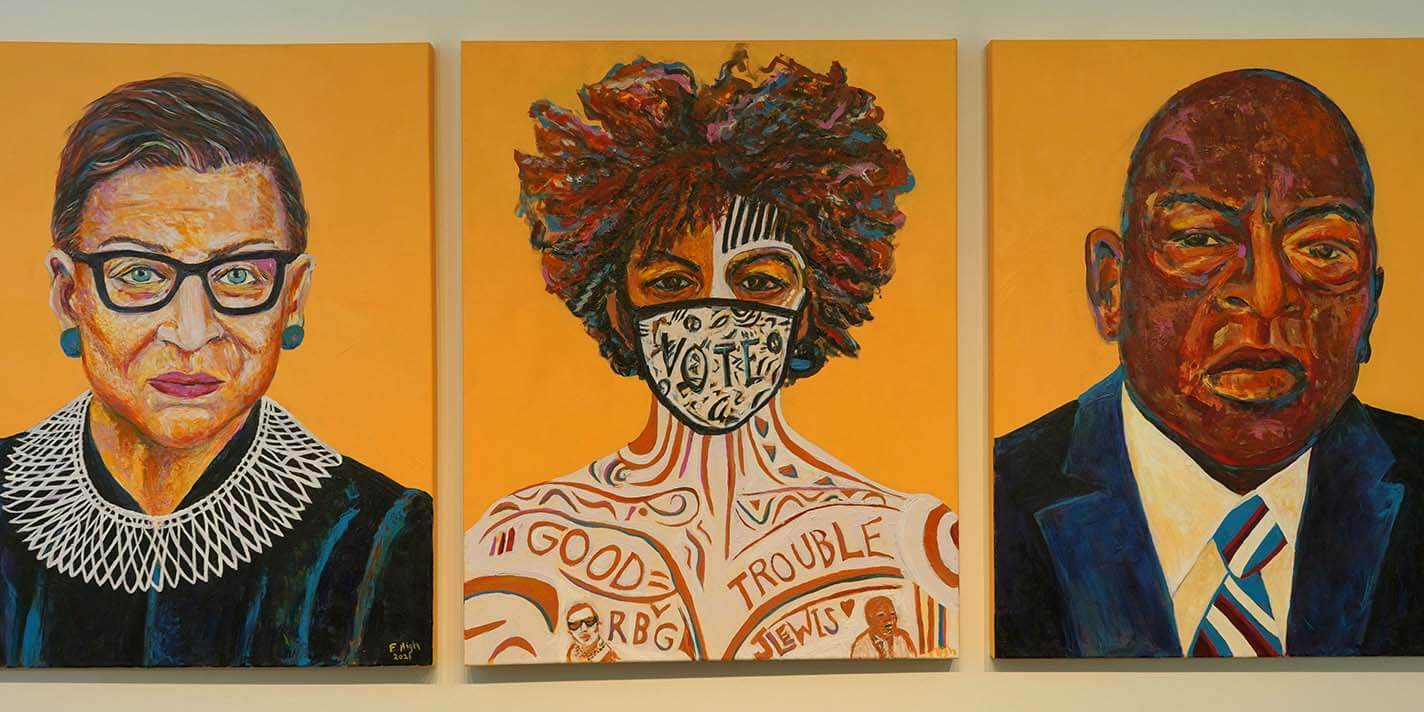

High retired from her role as the Evjue-Bascom Professor of African and African American Art History and Visual Culture in the Departments of Afro-American Studies, Gender and Women’s Studies, and Art in 2012, 43 years after she sat on the committee that oversaw the Department of Afro-American Studies’ creation. Since 1978, the department has awarded more than 500 bachelor’s degrees, 150 master’s degrees, 26 "bridges" to PhDs in English and history, 57 doctoral minors, and 69 certificates (the last program High established before her retirement) that span a range of research areas. Graduates go on to work in a breadth of professions including academic leadership and administration; education; community organizing; writing and publishing; curation; art and art history; literary and historical scholarship; poetry; and medicine, to name only a few. High was recognized for her art and publications as an artist-scholar, and for her tireless commitment to elevating and celebrating Black art and culture, with the 2021 Lifetime Achievement Award at the James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art at Howard University.

In today’s climate of renewed calls for change and demands for justice that echo those that mobilized her generation, High sees a continuation of the cultural activism that she and her colleagues committed to fostering in the Department of Afro-American Studies.

“Think about the many students who are out there. How many of those students are the daughters or the sons of parents who took Black studies? Or how many of those students also took Black studies or Chicano studies or women’s studies?” High asks.

“By changing the university, we have brought so much knowledge into the universities that many young students over the generations have learned, and [they] also have become activists in their own thought. There’s much more of this humanitarian orientation. And I don’t think I’m being idealistic when I say this, but I think that many of the students today… are carrying forth the journey that we started.”

This story was originally published in the February 2022 issue of Badger Vibes. Learn more about this monthly newsletter from WAA, and sign up for the mailing list.