UW Majors: Botany and Forestry

Author

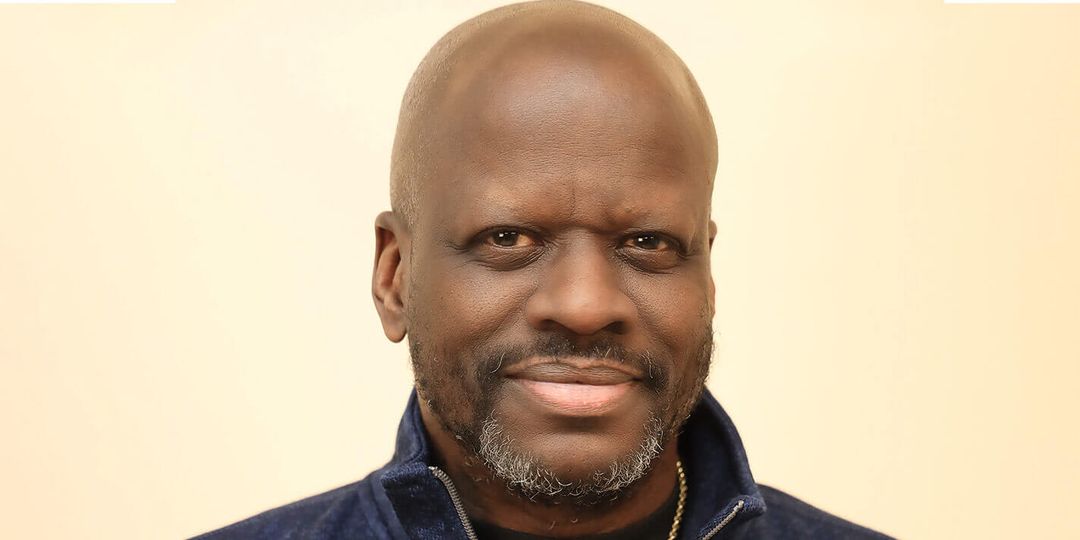

Distinguished Teaching Professor and Director, Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry

During her graduate studies in botany at the UW, Kimmerer lived in a small house on the grounds of the Arboretum and worked as its resident security guard. One night, as she made her rounds, Kimmerer found a garage door left open. She peeked in and saw a bulletin board with a photo of what was then the tallest American elm tree in the United States. The photo called to Kimmerer in a special way: the tree was named the Louis Vieux Elm, in honor of a Potawatomi tribal elder who also happened to be one of Kimmerer’s ancestors.

Shortly after, Kimmerer was invited to a gathering of Native elders to hear them talk about plant wisdom. The timing of these occurrences felt connected and sparked a profound realization. “To walk the science path, I had stepped off the path of Indigenous knowledge,” she says. “But the world has a way of guiding your steps.”

For Kimmerer, those steps included becoming a distinguished professor of environmental biology, best-selling author, and founding director of the SUNY Center for Native Peoples and the Environment. In 2003 she published her first book, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses, which blended lyrical personal essays with groundbreaking observations about these remarkably resilient, if underappreciated, plants.

Over the next decade, the ideas Kimmerer first explored in Gathering Moss gradually evolved into Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, which articulated a vision for incorporating Indigenous plant knowledge and storytelling into Western science. It has sold almost half a million copies worldwide, and in 2022, Kimmerer received a MacArthur “genius grant.”

She describes herself, “at root,” as a plant ecologist focused on the field of biocultural restoration, with the aim of healing human relationships with the land. It’s a goal that feels especially urgent as the effects of climate change begin to accelerate. “The consensus is that we have all the science and technology we need, but we don’t do anything [collectively about climate change] because we’re relying too much on the intellectual knowing alone,” she says. “We have failed to activate our emotional responses to propel us to change. As Aldo Leopold said, we need poets who are foresters.”

Kimmerer’s work offers an invitation to those who are looking for ways to reimagine their own personal connections with nature. She suggests beginning with a fundamental shift in perspective, from viewing nature as a resource to be exploited to experiencing it as community of kinfolk to which we belong — and for which we are responsible.

“People have a great longing to be in a right relationship with nature, and they just don’t know how,” she says. “The way we treat land is how we treat each other. It’s the idea of kinship with each other and with other species. We can extend that idea of kinship to the land itself.”

It’s a path she also believes can offer people a sense of hope for the future. “An awful lot of the environmental movement has been fear driven, and rightly so, but we also have to have this sense of moving towards something,” she says. “A right relationship with the natural world can be so fulfilling and joyful, and I can’t help but think that love of land and love of home is where we can all agree.”