A record collection immediately draws the eye in any room it occupies. Like books on a shelf, a neat display of albums begs to be browsed, rummaged, and revered. While many personal collections are stashed in carefully curated crates in bedrooms and attics or lovingly displayed in cozy corners of living rooms, the UW gave its campus record collection its very own library. (Cue jealous groans of vinyl enthusiasts everywhere.) And thank goodness they did, because there’s so much more than vinyl stowed in this hidden gem at the heart of campus.

Nestled in the basement of Memorial Library, the Mills Music Library is surprisingly bright and spacious for a subterranean location, and unsurprisingly cheerful thanks in no small part to the audiophiles who see to its care. Despite the characteristic hush of a library, Mills likely houses more sound per square foot than any other quiet space on campus with its circulating, digital, and special collections of music and all of the technology and literature to support it.

The Mills Music Library is also a retrospective of recorded sound. What puts the “retro” in retrospective varies from generation to generation, and Mills has it all. Some Badgers’ eyes grow to the size of 45s at the sight of a magazine article from the 1890s that emits music when traced with a bamboo needle. Some relish the satisfying clack of sifting through CD cases. Others may puzzle over opening a cassette tape.

But strum the opening notes of “Here Comes the Sun,” and heads of all generations turn. Press “play” on A Hard Day’s Night,” and a room freezes in anticipation of a chorus it knows all too well. Drop a needle on “Hey Jude,” and any listener within earshot starts to nod along, if they’re not already singing. The Beatles didn’t invent recorded sound, but they were integral in shaping it. An exciting new acquisition of rare Beatles records in Mills helps to tell that story through a band that is as ubiquitous across music history as music is to, well, everything else.

Beatles in Badgerland

The Beatles never played in Madison. It was only in 2019, 55 years after the band first touched down in the United States, that Paul McCartney made his Badgerland debut with the second-most pyrotechnics the Kohl Center has ever seen. (The Varsity Band Concert still reigns supreme.) With this new collection in the Mills Music Library, the Fab Four are making a long-overdue appearance at the UW and bringing new knowledge about one of the most studied bands in music history.

The collection encompasses more than 600 LPs (long plays) and other Beatle-y media that span their early years to their solo careers. But these aren’t any old, beat-up albums, nor are they the glossy new ones being sold in stores today. This acquisition comprises bootleg recordings featuring live shows, interviews, press conferences, home recordings, outtakes, unreleased tracks, and more in-depth, insider knowledge than one can read into the lyrics of “A Day in the Life.”

It’s a collection lovingly curated and meticulously documented by someone with an eye for the obscure, the unique, the hard-to-find, and the rumored-to-exist — someone with a knack for investigation and a vested interest in four musicians from Liverpool — and they don’t call Jim Berkenstadt the rock-’n’-roll detective for nothing.

For more than 30 years, Berkenstadt has partnered with some of the biggest names in music to research, write about, and consult on the history of pop music. In addition to publishing numerous best-selling books on music history, he has credentials that include historical consultation on Martin Scorsese’s George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011), research for Ron Howard’s The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years (2016), and audio research for Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back (2021). But his fascination with the Beatles dates back to well before his career, and it’s never been strictly professional.

“Before I was the ‘rock-'n'-roll detective,’ I was just a big fan,” Berkenstadt says. He first donned his detective hat in the eighth grade while gathering friends around a copy of Abbey Road and searching for clues as to whether, per urban legend, Paul was really dead.

“The teacher asked what we were doing, and I explained that I was showing them the clues. We were trying to determine whether they were valid or ridiculous.”

It was around this time that Berkenstadt was introduced to bootleg LPs, which challenged his assumption that he already owned everything the Beatles had ever recorded — so he spent years collecting more. He amassed what eventually became one of the most robust collections of bootleg Beatles LPs in the country, a feat that culminated in the publication of his first book, Black Market Beatles, which documents these rare recordings. The book found its way to the desk of Neil Aspinall, the Beatles’ former road manager and then-CEO of their record label, Apple Corps. The rest is, quite literally, history.

But after years of providing research and enjoyment, the collection was sitting idle, and what good is sound condemned to silence, anyway? A Madisonian with an affinity for the local research university, Berkenstadt determined that the only place better suited to house the collection was Mills, where it could enrich scholarly research and indulge fan curiosity about the Beatles and the world they helped shape.

“I just think of the Beatles in terms of Beethoven and Bach and some of the great composers of different centuries. And there’s no bigger name in music in the 20th century than the Beatles,” Berkenstadt says.

Why not preserve it and let the university share it with people who might want to research the Beatles or understand why they were such a great band?”

The Jim Berkenstadt Beatles LP Collection now resides in Mills’s Special Collections. Along with the small but representative array of the Beatles’ discography in their circulating collection, the new acquisition offers a comprehensive look at four artists who influenced music

and culture both well before and long after their shared moment.

Meet the Beatles

Few bands are so ingrained in popular culture that any person on the street could likely recite the names of the members with the ease that they might also recall the four seasons or the cardinal directions. With as many Beatlemaniacs and Berkenstadtian researchers as the band has amassed in 60-plus years, it would be fair to assume that everything there is to know about them has been committed to public memory. It would also be wrong.

“You don’t need to come into Mills to listen to the Beatles,” says Nate Gibson, an ethnomusicologist and audio-visual preservation archivist with the UW’s general library system. “But you’ll likely experience their music differently if you do.”

Digital versions of the band’s albums may satisfy the casual listener, but they leave much to be desired for those who recognize the artful composition of an album, or one who wants to learn how to interpret it. This collection offers an unfiltered look at how the Beatles found, honed, and reinvented their sound. The bootlegs are audio snapshots of the band before fame, between recording sessions and concerts, and after their breakup.

According to music technical services librarian Matt Appleby MA’00, who inventoried the collection upon its arrival, notable gems include recordings of early club shows in Hamburg, Germany; chaotic press conferences; a solo-era John Lennon’s home-recorded piano musings, permeated with half-forgotten Beatles licks; and the unreleased ballad a young McCartney wrote in hopes of it being sung by Frank Sinatra.

“You can find other interviews of him talking about [that song], but here, [you can] hear the song that he’s talking about. You can make a lot of links like that through this collection,” Appleby says.

The bootlegs — raw recordings captured and sold unofficially (and often illegally) — provide a stark contrast to the pure and polished sounds the band spent hours carefully crafting in the studio. But it’s for this very reason that the Berkenstadt Collection also serves as the primary text for the final takes that the band did release — what became some of the most iconic music in the world.

“John Lennon and Paul McCartney weren’t sitting down and writing out compositions, necessarily. They were jamming, as it’s been famously seen in the documentary The Beatles: Get Back,” says Tom Caw, music public services librarian with Mills. “Paul McCartney’s strumming away on his bass, and the next thing you know, ‘Get Back’ just kind of comes together as they all chime in with different ideas.”

Bootleg recordings of these jam sessions and early studio takes trace the evolution of the tracks that play from our speakers today. They also offer an exclusive look into the creative process of some of the most prolific and influential artistic minds of the century.

“I took classes in art [in college], and we would follow a Picasso from its very first drawings all the way to the finished painting,” Berkenstadt says. “[Through these bootlegs], I was looking at the Beatles’ music in that same way.”

In My Ears, and in My Eyes: A History of Recorded Sound

This collection is about more than the Beatles. As much as Mills Music Library is a seemingly infinite repository of songs to be enjoyed (and by all means, enjoy!), it’s also a place to ask and answer questions of the histories that those songs and other musical resources harbor.

“Art and technology have changed music,” says Gibson. “Popular music and popular culture can be profoundly influential in creating societal change.”

This is a fundamental lesson in the curricula of Susan Cook, the Pamela O. Hamel/Music Board of Advisors Director of the UW Mead Witter School of Music, a professor of musicology, and an expert in contemporary 20th- and 21st-century music.

“I’m very keen for having students realize that we wouldn’t be able to teach music history if we didn’t have recorded sound,” Cook says. “Music can circulate without the actual physical bodies that play it, which means that it can, at times, cross racialized and geographical boundaries.”

In his studio in Mills, Gibson bears witness to this power of recorded sound every day through the digital preservation of audio in all formats, including lacquer pressings, disc recordings ranging from 16 to 80 rotations per minute and beyond, cardboard and aluminum records, open-reel tape, digital audio tapes, and more. He sees in the Berkenstadt Collection a chance for students to study the variation in sound across time and technology.

“The Beatles were issued in lots of different configurations, so [we can] study how those recording technologies actually impacted the sound,” Gibson says. “You can study the difference between deep-groove and vinyl pressing and flexi discs, direct metal mastering, reprocessed stereo, and all of the different changes that were happening in recorded technology.”

The collection also offers insight into the mixing and marketing of music. Many Beatles albums were released in two formats: a mono mix that adhered most authentically to the band’s artistic vision, and a stereo mix that sacrificed the nuance of the original for a more profitable record.

“There are subtle differences. If the music is in the background and you’re not really caring — you just want to sing along to the song — then you may not notice them,” Gibson says. “But if you are interested in why people put the sitar in the left channel and put the vocals in the far right channel and how it had different effects, this is one way to look at that.”

Even the less-polished pressings within the collection tell stories about artistic decision-making that speak to both the character of the band and the technical process of creating an album. According to Berkenstadt, live albums demonstrate the ways musicians adapted studio songs to stages and vice versa, whereas outtakes implore listeners to consider the tracks that did make the final cut and the implications of including or excluding the ones relegated to bootlegs.

For Caw, the physicality of the collection also offers opportunities to teach students how records speak for themselves, through album artwork and detailed liner notes, well before hitting the turntable.

“I’ve asked students, ‘If you’re listening to a musician on Spotify and you want to know who played the drums on a song, where was it recorded, who recorded it, who produced it, who mixed it, who mastered it … might you be able to find that while you’re in Spotify?’ Then I see them thinking: ‘Huh. No.’”

Could they look it up online? Sure, Caw says, but even this opens conversations about information literacy and research that inevitably circle back to the primary texts.

“There is something to the tangible, to the physical format, to seeing it as it was released in its context originally,” Caw says.

This is especially true, says Jeanette Casey, head of Mills Music Library, for the many people for whom music has never been physical. In Cook’s classes, it invites them to engage with sound in ways that both deepen their appreciation for the music and develop their understanding of recording technology and album composition.

“I’m excited about having the physical evidence to share with students so that they get the fuller sense of what these LPs meant in their time: for us to hold them in our hands, to look at them, to turn from the front cover to the back cover, and then to take the LP out and play it on our equipment,” Cook says. “It gives the full scope that the music isn’t just the sound. The music is the technology. The music is the material culture.”

In short, it demands to be more than just heard.

“Music doesn’t have to be a passive, background thing,” Gibson says. “When you put the record on, you have to be there when it ends to lift the needle. … It’s an immersive experience.”

And that’s Mills: an immersive experience, an educational endeavor, and an enjoyable hour spent picturing yourself in a boat on a river while parsing the historical moment a song, artist, or album captures, and how it still reverberates today.

Selections from the Jim Berkenstadt Beatles LP Collection will be included in the exhibit Press Play: Recorded Music from Groove to Stream, which will be on display in Memorial Library’s Special Collections Room during the fall semester.

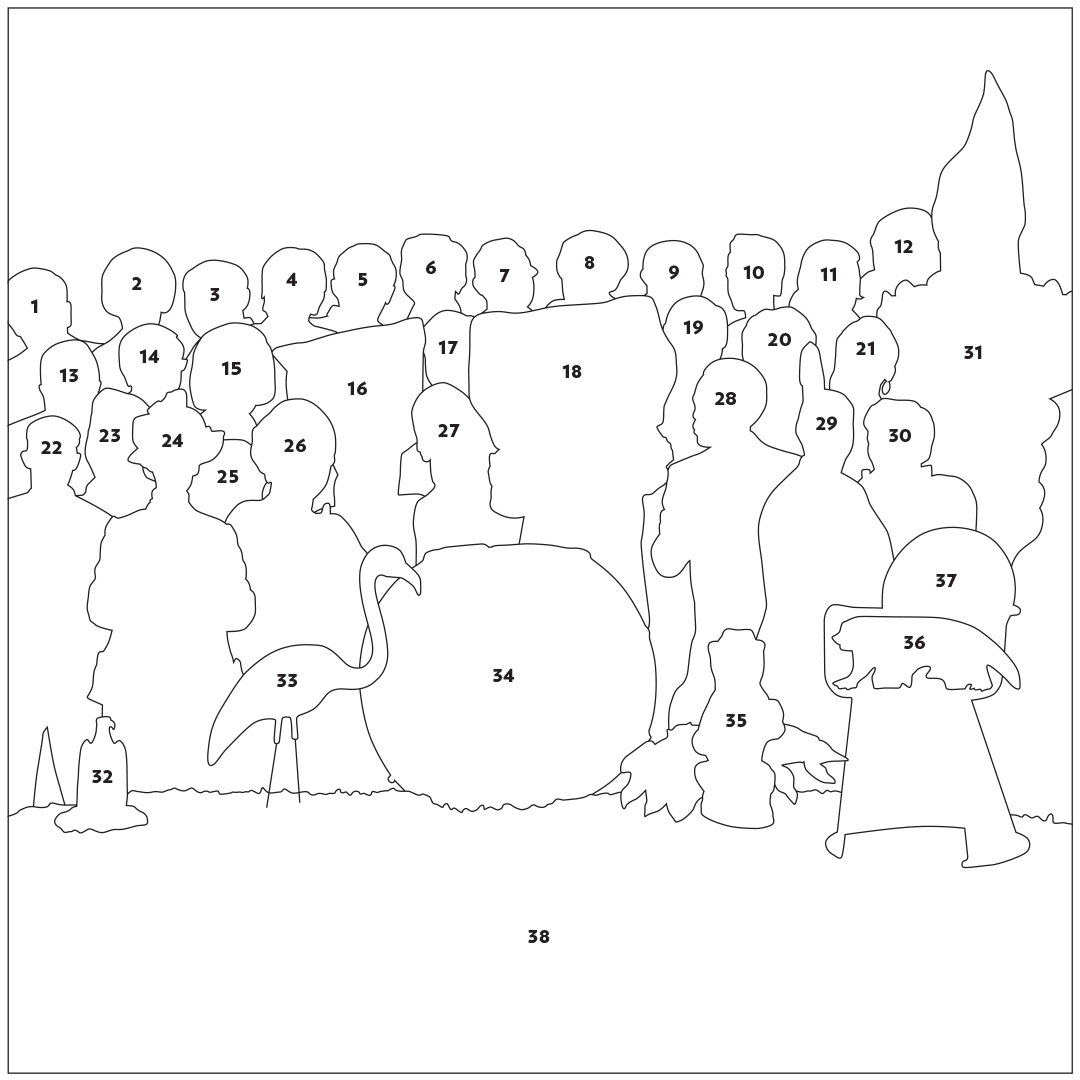

Sgt. Bucky’s Badger Hearts Club Band

The UW’s tradition of educating Badgers who change the world extends well past “20 years ago today.” This sampling of Badgers from Alumni Park is an homage to the alumni community at large. We hope you have enjoyed the show.

- Walter Mirisch ’42, movie producer

- Emily Hahn ’26, author and journalist

- Thomas Vonder Haar MS’64, PhD’68, climate scientist

- Marcy Kaptur ’68, U.S. congresswoman*

- Abraham Maslow ’30, MA’31, PhD’34, psychologist

- Lorraine Hansberry x’52, playwright

- Pongsak Payakvichien MA’71, newspaper editor and executive

- Frank Lloyd Wright x1890, architect

- Elzie Higginbottom ’65, real estate executive*

- Vel Phillips LLB’51, first Black woman graduate of the UW Law School and civil rights advocate

- Ada Deer ’57, first chairwoman of the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin; American Indian rights advocate

- Allee Willis ’69, songwriter*

- Jim Sensenbrenner JD’68, former U.S. congressman*

- Tony Evers ’73, MS’76, PhD’86, Wisconsin governor*

- Geraldine Hines JD’71, first Black woman on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, civil rights advocate*

- Buckingham U. Badger, mascot c. 1949

- William Campbell MS’54, PhD’57, scientist, researcher on parasitic diseases*

- Buckingham U. Badger, mascot c. 2017

- Gaylord Nelson LLB’42, former Wisconsin senator and governor, founder of Earth Day

- Linda Thomas-Greenfield MA’75, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations*

- bell hooks MA’76, feminist author and scholar

- William Harley 1907, cofounder of Harley-Davidson Motor Company

- Adam Steltzner PhD’99, NASA engineer

- Florence Bascom 1882, 1884, MS1887, geologist

- Chelsea Rademacher ’13, editor emerita of Badger Insider magazine

- Florence Chenoweth MS’70, PhD’86, Liberia’s former minister of agriculture, food security advocate

- Mildred Fish Harnack ’25, MA’26, resistance leader in Nazi Germany

- André De Shields ’70, actor*

- Kiana Beaudin ’10, MPAS’15, executive director of health for the Ho-Chunk Nation*

- Jesús Salas MA’85, labor organizer and migrant workers’ rights advocate*

- Lady Liberty’s torch from her yearly appearance on Lake Mendota

- Old Abe the eagle, who is usually perched atop the Camp Randall arch

- Plastic lawn flamingo: once a Pail and Shovel Party prank, now a UW icon

- UW Marching Band drum

- Sandstone gargoyle from the original UW Law School building built in 1893

- A mother badger and her cubs in The Four Lakes by Andrea Myklebust and Stanton Gray Sears (located outside of State Street Brats)

- A Badger-red sunburst chair

- Even the flowers on campus throw the W.

*These Badgers are members of the most recent group of inductees into Alumni Park.