Molten glass is not easily classified among the defined states of matter. It is inherently ephemeral, existing in a transitory state between liquid and solid. It’s inaccessible to the human hand and yet entirely responsive to the hand’s influence on its cooling curve. To Helen Lee, director of the UW Glass Lab, this “in-betweenness” is one of the many uniquely “glassy qualities” that render her medium rich with exploratory potential.

“People will call [glass] an amorphous solid and all these other terms, but I like it when it’s called a different state of matter, just because my imagination gets so curious,” Lee says. “We understand solid, liquid, gas. Those are commonplace, everyday things. But it’s not that commonplace to interact with the glassy state.”

Encounters with the glassy state were even less commonplace prior to 1962, when the UW’s Harvey Littleton established the country’s first academic glass arts program, bringing glass from its traditionally industrial environment and placing it in the hands of artists.

“This program happens to be situated in a really highly interdisciplinary fine arts program,” Lee says. “It is a huge privilege to be in a facility in an academic learning environment where you’re not answering to [a] commercial market. You are instead granted the freedom to get curious around what the material can do.”

Littleton’s reclamation of glass as a medium for artists and academics marked the beginning of the movement known as American studio glass. Today, the Glass Lab is at the forefront of a new era of contemporary studio glass as artists bring the medium into areas of academia that stand to benefit from the ubiquitous and multi-elemental material’s abilities to reflect, refract, and redefine other realms of scholarship.

“Back then [in the 1960s], it was groundbreaking and innovative to even be able to control glass or understand it on a personal, intimate, one-on-one, material-in-my-hand relationship,” Lee says. “Now, 60 years later, we’re actually able to see what different types of connections we can make or what different paths of scholarship we can navigate because we have the disciplined skillset of knowing the material to such an intense degree of intimacy.”

During this fall’s Glass Madison exhibitions, Lee is celebrating Glass Lab students and alumni of the past decade whose work continues the program’s radical traditions by challenging and redefining what it means to be a contemporary glass artist. The following individuals are a sampling of those who do so by pairing their practices with fields of study that reveal the interdisciplinary utility and potential of “glassy qualities” beyond the kiln and blow pipe.

Glow

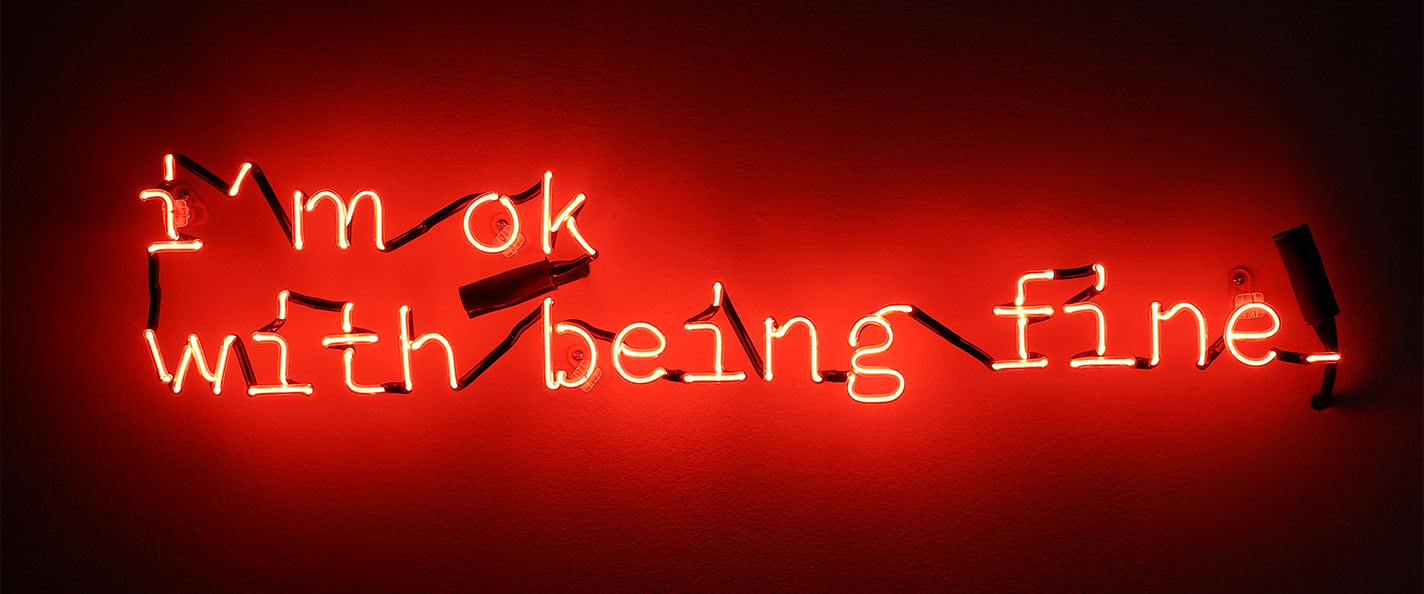

Stephanie Lifshutz ’15, MFA’16 has little use for word-processing programs. When she writes, she prefers pen and paper. Or neon light.

“I was attracted to [neon] because I’d really been struggling to communicate what I wanted to in an effective way,” she says.

Lifshutz came to the UW with an undergraduate art degree that encompassed a museum’s worth of media — but none of it was quite bright enough for the statements she wanted to make. In the Glass Lab, she found a medium through which she could express the quiet parts of her life out loud. When bent into neon tubes, her “suggested commands” and softer language demand the immediate and undivided attention afforded to the imperatives and directives that traditionally grace neon works.

“Neon has such a history of signage,” she says, “and being able to use a medium to literally put something in your face and say what I want to say makes the most sense … [to] be as direct and loud as possible.”

From the pages of her journals, Lifshutz draws words and phrases that distill entire entries into poignant bits of prose that elicit her voice while reaching a larger audience. Works like I can’t wipe my eyes right now, but I don’t mind, and Numb for too long call attention to the intimate moments that otherwise exist exclusively within the privacy of a diary. Viewers recognize and resonate with the vulnerability of language that’s scrawled in the artist’s hand, while feeling welcomed to partake in signage that demands to be seen. Still, despite the pieces’ harsh light and commanding presence, choices about lettering, size, and color help Lifshutz preserve the tones of her original messages.

“We are making something in a bright, bold light,” Lifshutz says. “It stands out no matter what, so working with color, scale, and font really allows me to also play with subtlety.”

The intense isolation of the early days of the pandemic facilitated a turning point in Lifshutz’s practice. Where her prior work had primarily reflected her interactions with others, the sudden lack of interaction pushed her writing to become more introspective and vulnerable. It was only fitting, then, that almost all of the messages she began to cast in fluorescent light were done in her own script.

“I did want to stick to my own handwriting because it was so much more about me than it had ever been before,” she says. “Sometimes it’s a little illegible to put my handwriting out there, but I felt more connected to the work than I have in the past because of that.”

Lifshutz is a member of She Bends, a collective of women and femme-identifying artists who are disrupting the historically male-dominated and exclusive world of neon by uplifting the work of fellow underrepresented artists. She also owns and operates a neon fabrication shop, Pumpkin Studios, in Brooklyn, New York.

Source Material

Anna Lehner MA’18, MFA’19’s work exists in stillness — in the calm before the chaos, the quiet before the quake. During their first year as a graduate student in the Glass Lab, their practice lingered in the liminal space between uncertain and established. It took cross-campus partnerships to shake the foundations of Lehner’s work, and since then, Lehner has never been more grounded.

“When I started taking geology classes, I [realized] I’m always making work that’s talking about the edge of something … about the buildup of stress or the moment of pulling something apart,” they say.

Though Lehner had been blowing glass since their undergraduate art days at UW–Stevens Point, the medium took on new meaning through the geological lens they adopted at UW–Madison.

“Any glass has a transition point,” Lehner says. “If it’s not slowly cooled down, it holds all the stress within it. Then, it’ll randomly combust. … That kind of relates, in different timescales, to what’s going on underneath our feet.”

Lehner had only been “lightly touching” on these themes of geological time in their work when they took a class with Harold Tobin, a professor of geological engineering. With Tobin’s expertise, Lehner’s work began to channel the power and presence of earth-shaping forces, instead of merely considering them. Pieces like Timescale and Brittle Boundaries are activated by seismic activity across the globe in real time, distilling destruction into quiet, contemplative spaces. Other works, such as Material Memory and Soft Rock, are fashioned from or inspired by naturally occurring glass found in fault lines.

“[This glass] is a signifier of fragility and strength that kind of marks that moment in time,” Lehner says. “I think about how [with] glass we use in the studio, every little motion, breath, thing we do to it is very much encapsulated in it. It has a material memory of action that is really quite amazing.”

In 2020, Lehner traveled to New Zealand on a Fulbright Research Grant to study seismic activity along the Alpine Fault in the Hikurangi subduction zone. Here, they accompanied a team of researchers to take core samples from alpine lakes in order to study sediment movement and deposits affected by underwater landslides caused by earthquakes. Lehner spent the second half of their residency casting Shifting Foundation, a glass depiction of a sediment core extracted during their field research.

“[This experience] opened my mind to how scientific inquiry can be questioned, analyzed, and presented in a creative way that just offers another way of looking at things,” Lehner says. “The scientific process is so literal, but it has the very same basis, foundation, and creativity [as the artistic process] — we’re asking questions and we’re investigating.”

At the Looking Glass

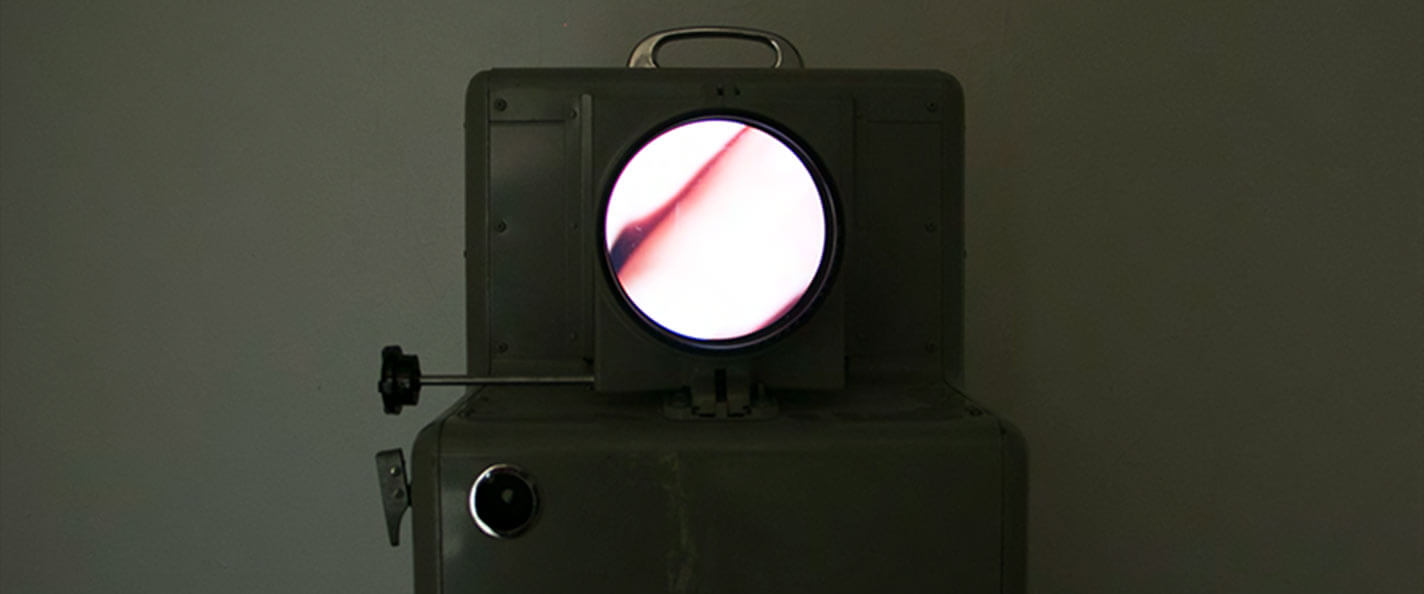

Glass is not an easy medium to work with, much less to learn. But when Chelsea Thompto MA’18, MA’19, MFA’19 first picked up a blow pipe in the Glass Lab as a graduate student in 4-D art, the medium’s challenges and intensity were similar to the themes she was already grappling with in her sculptural practice.

“My work is a little bit less interested in identity in particular and more about the way identity is perceived and visualized,” Thompto says. “Glass is just such a mediator of all of that in our culture.”

Since coming out as transgender during her undergraduate art education at the University of Iowa, Thompto’s work has considered the burden of other peoples’ perceptions of her through sculpture, print, and digital media.

“If the hardest part of being trans is the violence of perception and visualization, then making work that helps to manipulate, change, or call into question the way perception or visualization operates becomes a really powerful metaphor and tool,” she says.

In Thompto’s work, glass doesn’t simply play host to her human-responsive code or other digital media, but purposefully engages with it. In Read, a two-way mirror — a common tool in security work — reflects a projection of Thompto’s body. As Thompto writes in her artist’s statement, the mirror duplicates the surveillance of her body while simultaneously denying privacy to the viewer. In her fog light series, an obfuscated image on a small screen is revealed to be not glitchy tech or flawed code, but ridged glass that mimics the refractive bulbs of lighthouses and headlights that cut through fog.

“On our phones or glasses or the screen on our computers, there’s always that film of glass,” Thompto says. “By making that [glass] activated, you start to really have a lot of opportunity to disrupt people’s perception.”

It doesn’t always take a two-way mirror or overt texture to call attention to screens that are more often looked through than looked at. According to Thompto, even seemingly flawless blown glass reveals imperfections — bubbles, waves, and fissures — when used as a vessel for projection. To Thompto, these distortions comment not only on the elements of personhood that are invisible to the naked eye, but on the potential for fault and fallacy in our deeply held beliefs.

“Any time that we think of something as clear or transparent, being able to call into question what that actually is is a way for me to [suggest], ‘Well, if that category isn’t true or real, or if it’s unreliable, then what else that you’re thinking about might be unreliable?’ ” she says. “For me, distorting an image — and especially distorting it in a way [that’s obvious] — really becomes key in thinking about trans identity and the ways that trans identity has a lot applied to it.”

Between Dimensions

It wasn’t neon’s signature bright lights and bold colors that first captured the attention of Ben Orozco ’19. A graphic designer with a keen eye for pattern, Orozco was more enchanted with neon’s ability to transcend dimensions and transform the space around it through a single line.

“For a neon unit — which appears flat from the front — you turn it on its side, and you can see almost two and a half dimensions,” he says. “I started getting really excited about this moment that felt flat and three-dimensional at the same time.”

During his first classes in the Glass Lab, Orozco was intrigued by the material’s potential to elevate the aesthetic trademarks of his design work. Like a moth to a fluorescent flame, he was drawn to neon’s clean, pure lines; the poreless and infinitely scalable nature of its glass vessel; the absence of shadows and deceptive distortion of spatial hierarchies; and the meticulous process of translating two-dimensional patterns into luminous sculptures.

“That was truly transformative for me,” he says, “being able to explore building form through literal material as well as through the illustrated form.”

In Identified Space, Orozco’s type-design skills are illuminated in a square of overlapping, neon-orange pronouns. His Sag collection features clean grids that create illusions of dips and bends in a near-perfect surface. Tropicalia is a lush jungle of luminous plant life in striking neon greens, not unlike those in his hometown of South Miami, Florida.

With the help of a Fulbright-Hays Research Fellowship, Orozco spent nine months at the Glass Factory Museum in Boda, Sweden. Here, he divided his time between piecing together a safe and sustainable neon shop with a hodgepodge of the museum’s dated equipment, researching its archives of Swedish glass art, and utilizing the Swedish glass overlay technique graal, which layers colors that are revealed through etchings on the piece’s surface, allowing Orozco to further explore glass’s canvas-like potential for hosting intricate designs.

“I started thinking about my love for optical patterns and how I could combine that with this history of surface design and surface techniques,” Orozco says. “I also lean more into my sculptural and installation practice by extending or creating patterns in the background that create a more interesting relationship: you’re not just looking at the object, but you’re looking at how the object performs in space.”

The culmination of his residency, YTA, or “surface” in Swedish, incorporates blown glass, stylized environments, graal, and neon sculpture to challenge the eye’s spatial and dimensional perception.

Elemental

As a budding art student, Felicia LeRoy ’14 leaned into the laboratory element of the UW Glass Lab by mixing glass with concrete and experimenting with the resulting material’s ability to capture and distort light. She used this material to build fiber optic cables and glass rods that she fashioned into frosty panels, and then she staged performances in which she suspended and walked over the panels, testing their breaking points.

“With glass, so much of it is performative in nature. There’s a real relationship between you and the material,” she says.

This fascination followed her to graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she explored relationships between the body and substances that bore similarities to glass, such as water and ice.

“[There are these] reflective qualities or abilities to bend light, to move, to be fluid and be ice,” she says, “to be one thing, but to have all these different properties.”

Here, she embraced pure glass’s ability to reflect and capture organic phenomena. For her thesis, “How Long Can You Hold Your Breath?” LeRoy returned to her laboratory practice by running hot-casting experiments in which she used air to move the malleable glass. Not satisfied simply observing the push and pull of breath with her medium, LeRoy took up free diving to deepen her understanding of the force she was using to shape a molten state of matter. In pushing her limits of holding her breath, she learned about how air is contained and strives to be free. Her body of work also includes a series of blown glass pieces that each contain the collective breath of two lungs.

“With breath, especially in thinking about glass and glass blowing, there’s this really interesting relationship directly between you and the piece. [You’re] literally putting yourself into a piece of work,” she says. “Breath gives life to a piece in the same way [that it’s] giving yourself life.”

LeRoy further explored her fascination with the role of the artist as an extension of the work and of the tools she uses during a monthlong residency in the Arctic Circle. LeRoy joined a collective of artists conducting individual research projects aboard a ship circumnavigating Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. For her research, she recorded data on glacial drift at the cusp of the rapidly receding polar ice by using a buoy modeled after those of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Global Drifter program.

“This whole place is an extension of our collective humanity,” she says. “You can see it [in] all the trash exiting the transpolar drift and landing on one of the most remote islands in the world.”

Her artistic interpretation of this research will combine vitreography (engraved-glass printmaking) to map the documented movement and video to supply both the numeric data and the sensory experience of the icy environment in which it was collected.