More than a century and a half after the UW’s first students met, you can still find their legacy on campus — but can you find their descendants?

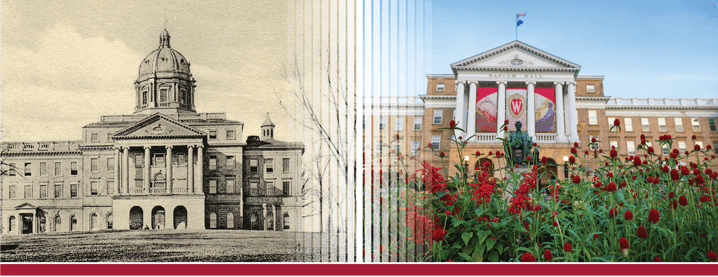

When you stroll along our campus sidewalks, do you ever take a moment to gaze up at those magnificent and timeworn buildings, to admire Henry Mall’s sturdy, brick façades or imagine students and professors heatedly discussing the Civil War or politics in front of a fireplace in North Hall?

Maybe that’s just me.

I feel lucky to live and work in a space that thrives on the energetic pulse of its students and cutting-edge researchers, yet respects its traditions and cornerstones (literally: workers recently completed renovation projects on North and South Halls, both built of locally quarried sandstone in the 1850s).

So when my colleagues here at the Wisconsin Alumni Association (WAA) began work on this year’s Founders’ Day celebrations (when alumni commemorate the UW’s earliest days), I couldn’t shake this question from my mind: how much do we really know about the university’s first students, pioneers who had no idea that their studies would lay the groundwork for what was to become a top-ranked, world-renowned institution? Do any connections remain between them and the UW that we know and love today?

Class Roster

Class Roster

Levi Booth* | Madison, Wis.

Byron E. Bushnell | Madison, Wis.

Charles E. Fairchild* | Madison, Wis.

James M. Flower 1856, MA1859 | Sun Prairie, Wis.

William H. Holt | Madison, Wis.

Henry McKee | Platteville, Wis.

Stewart McKee | Platteville, Wis.

Daniel G. Jewitt | Madison, Wis.

Charles D. Knapp | Madison, Wis.

Francis Ogden | Madison, Wis.

Robert Ream | Madison, Wis.

Robert D. Rood | Madison, Wis.

Charles D. Smith | Madison, Wis.

Hayden Kellogg Smith* | Madison, Wis.

William Stewart | Ancaster, Canada

George W. Stone | Madison, Wis.

Charles T. Wakeley* | Whitewater, Wis.

Richard F. Wilson | Madison, Wis.

Albert U. Wyman | Madison, Wis.

William A. Locke | Lake Mills, Wis.

*earned a degree from the University of Wisconsin

February 5, 1849

The UW's first-ever class commenced on a chilly February morning at the Madison Female Academy, which was situated on the southeastern corner of Johnson and Wisconsin — the future site of Madison's Central High School and, eventually, Madison College. The leaders of the all-girls school voted to allow the university to occupy the ground floor of the small, two-story, rectangular brick building at no cost.

The original regents believed young men graduating from the state's relatively new public-education system weren't ready for university-level instruction, and opted instead to develop a preparatory department to be run by John Sterling, a Princeton graduate living in Waukesha who earned a $200 salary in his first year teaching at the UW.

Who signed up for his classes? Most of the boys came from families that had migrated from the east coast looking for economic prospects. The oldest, at 22, was Charles Wakeley 1854, MA1857, who went on to become one of the UW's first two graduates and the founder of WAA. Charles Fairchild 1857, MA1861 was the youngest, two months shy of his eleventh birthday on the first day of school. Most of their families were likely middle to upper class, their fathers working in newspaper printing, lumber, real estate, or politics.

The regents set tuition at $20 per year (not a major financial hardship — divide by fifty-two, and that's about 38 cents a week, or the cost of a dozen eggs at the time). Mandatory courses included arithmetic, grammar, geography, Latin, and penmanship. More ambitious students were also given the option of studying bookkeeping, geometry, or surveying, should they desire. Classes were held not only at the academy but around town — at Sterling's home, hotel parlors, and law offices.

The following winter, the university's first chancellor, John Lathrop, arrived to begin his work, and the first true university class convened a year and a half later on August 4, 1850. North Hall was built using a $25,000 loan from the state and opened in 1851. South Hall followed in 1855. And in 1861, the UW admitted its first class of women.

Then and Now

I've always had a fascination with UW-Madison's history and a curiosity about genealogy. (My great-great-grandpa was a Hatfield. Turns out he never picked a feud with a McCoy, but he did walk all the way from New York state to settle in Wisconsin.) But I also manage WAA's social media accounts and website — things that should seem permanent, but to me are much more ephemeral than a slightly crumbling photo or the smell of a very old book.

So I set out to connect past, present, and future. I wanted to know who those boys became, as husbands and fathers, laborers and leaders. Did they share stories around the fireplace of good times had descendants know of the important place their forebears hold in our university's history, or that we celebrate them to this day?

There's actually very little in the university's annals to tell the story of our academic ancestors. Only a quarter of the original students graduated. Some of them remain virtually untraceable.

But by searching online census records and newspaper archives, I tracked down around one half of the original families, including two that maintain connections to UW-Madison in the twenty-first century: one a family of artists and community supporters, the other passionate civic activists.

Charles Fairchild 1857, MA’1861 ➛ Sage Fuller Cowles ’47

Sage Cowles came from a long line of artists — dancers, painters, sculptors, architects, and writers. She studied art history at UW-Madison, attended the New York City School of American Ballet, and danced on Broadway in the 1950s.

She was also the great-granddaughter of one of the UW’s founders.

“Growing up, I heard all kinds of stories about the Fairchild men, who made a name for themselves fighting in the Civil War,” Cowles told me from her home in Minneapolis when we spoke over the phone last fall. She passed away a few months later at the age of 88.

The Fairchild name is a familiar one to Wisconsinites. Jairus Fairchild operated one of Madison's earliest hotels and became the city's first mayor. His son, Lucius, fought for the Union in the Civil War and served as governor from 1866–72. A downtown Madison street and a northern Wisconsin village were both named after him. Jairus's youngest child never made headlines or history books, but he holds an honor few can claim: three years after the family moved from Ohio to Madison in the 1840s, Charles Fairchild became one of the first students to attend, and graduate from, the UW.

Charles was the youngest in the 1849 preparatory class. He didn’t officially attend the university until 1854, when he applied for admission as a freshman, and even then he was told he was three months too young. The story goes that he was so upset when he heard the news that he burst into tears, and so UW officials gave in and allowed him to enter.

During his time on campus, Charles ran the business department for the UW’s first student-run publication, The Students’ Miscellany, and eventually he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Inspired by his brothers’ Civil War service, he joined the Union navy and afterward attended Harvard. He worked as an attorney in Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and New York, where he established the banking house of Charles Fairchild & Co.

Charles and his wife, Elizabeth Nelson, had seven children. Their second-oldest daughter, Lucia, became well known around the world for her skill in the niche genre of miniature portraits. A 1923 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article described her as "one of America's greatest miniature painters," as well as "a woman of magnetic personality."

Lucia met her husband, Henry Brown Fuller, in art school, and they had two children. When the Fullers divorced in 1905, Lucia moved in with her daughter, Clara, who was living in Madison with her husband, Warner Taylor, a UW professor of English.

Clara’s niece, Sage, was the daughter of two more artists: Charles Fuller, an architect, and Jane Sage White, a sculptor. As a teenager, Sage’s passion was dance. But she came of age in the midst of World War II, and the stage didn’t offer a wealth of jobs then. So in August 1943, she opted to go to college, and it was her aunt and uncle’s love for Madison that ultimately convinced her to attend the UW.

“I was warmly welcomed in Madison,” she recalled. “It helped that I had family nearby — right on Langdon Street. The student union was extremely lively, and we had a great time at the lovely Terrace on the lake.”

Sage fell in with a "lively group of friends in the theater," and explored how she could further her dance education. "It never occurred to me a major university like the UW would have a dance program," she said. And not many major universities did — the UW had the nation's first degree program in dance, founded in 1926 by Margaret H'Doubler '10, MA'24. It placed an emphasis on anatomy, kinesiology, and physiology, and "that scared me, so I went on to major in art history," Sage said. "But I lived in the dance department."

After graduation, Sage and her friends (including pal Mary Hinkson ’46, MS’47, who went on to dance with Martha Graham’s company) formed a dance troupe and toured North America for two summers. Then, in 1952, Sage married her second husband, John Cowles, Jr., and they moved to Minneapolis, where the couple made a name for themselves supporting the arts and advocating for social causes and the advancement of women’s sports.

Sage said she was honored to be a part of our big Badger family. “I’m proud to be associated with someone who was an early founder of such a great university.”

James Flower 1856, MA’1859 ➛ Erica Simmons, UW-Madison Professor

When Erica Simmons accepted a faculty position in the UW’s Department of Political Science, she had no idea of her family’s connection back to 1849.

“I think of my own family history as deeply rooted in Chicago,” she explains over lunch at Steenbocks’s in the new Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery building. “It never occurred to me that we might have such an incredible connection to the University of Wisconsin-Madison.” The only connection she knew of was her paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Snider Simmons x’22, who attended but never graduated.

But Erica's great-great-grandfather was James Flower, another of the UW's first students. He was born in Hannibal, New York, in 1835, and moved with his family to Madison in the late 1840s. Twice, the family's finances forced Flower to drop out. He took jobs teaching at local public schools to pay tuition, and he eventually earned his bachelor's and master's degrees, then went on to law school in New York.

James met his wife, Lucy Louisa Cloues, soon after returning to Madison.

Lucy, a transplant from the east coast, taught at the UW’s preparatory department and volunteered her time giving aid to families of Civil War soldiers. The two married in 1863 and moved to Chicago, where Lucy began a long and lively career fighting for social and educational reform.

Among her many accomplishments, Lucy Flower became the first woman elected to an Illinois state office; she founded a legal-aid bureau to support women and children; she launched the Lake Geneva Fresh Air Association to provide vacations to children living in poverty; and as a member of the Chicago Board of Education, she rallied for improved teacher training and higher salaries for educators, the installment of bathtubs in schools, and the introduction of kindergarten.

“I come from a long line of women who dedicated themselves to making the world a better place,” Erica says. “I grew up on stories of how Lucy transformed juvenile justice in Chicago and how my grandmother, Ellen Smith, ran the bird division of Chicago’s Field Museum during World War II. I hope to forge an equally meaningful path of my own.”

Erica’s grandmother, Ellen Thorne Smith, was married to one of James and Lucy Flower’s grandsons, Hermon “Dutch” Dunlap Smith, and both took up the family’s mantle of activism.

“My grandfather is part of our family lore,” Erica says. “Like generations before him, he really cared about the city of Chicago and helped make it a great place.”

Hermon Smith served on a variety of cultural boards, including those of the Chicago Historical Society and the Field Foundation of Illinois. Inspired by his fascination with maps, he founded the Smith Center for the History of Cartography. And he and Ellen were high-profile political supporters of Adlai Stevenson’s gubernatorial and presidential campaigns in the 1940s and ’50s. When he passed away in 1983, the Field Foundation wrote, “Mr. Smith served countless organizations in a wide spectrum of charitable and civic activities. He brought … strong intellectual qualities combined with a deep and sensitive concern for the needs of other people. The people of Chicago have lost a great advocate.”

Hermon and Ellen’s daughter Adele Smith Simmons has long been involved in higher education and environmental activism. Before becoming president of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation in 1989, Adele earned her doctorate at Oxford, served as dean of students at Princeton College and president of Hampshire College, and did volunteer work in Kenya.

“My own mother’s commitment to social justice informs everything I do,” Erica says. “I am very proud to have so many inspiring women in my family.”

The Founders ➛ You and Me

Inspiration, I’ve found, is one of the things that Badgers do best. The more I learn about the students who met on that cold February day in a small room near the capitol some 165 years ago, the more I am in awe of the legacy they created. Without them, we might not have the education or experiences that made us who we are today. Sage Cowles and Erica Simmons might be linked by blood to the UW’s founders, but in a way, you could say we’re all just one (very) big Badger family.

“I can’t help but think about what an extraordinary institution the University of Wisconsin has become since my great-great-grandfather had his first days of class in 1849,” Erica says. “He took a risk on attending an unknown school, and now, more than 150 years later, I am benefiting from the courage that he and his classmates showed. It is wonderful to know that I am carrying on a family tradition of sorts.”

So what became of those other pioneering pupils in the UW's first class? Here are the stories of those students we were able to track down:

Levi Booth 1854, MA1858

- He was one of the first two graduates of the University of Wisconsin (along with WAA founder Charles Wakeley).

- After working in real estate in Madison for two years, he and his wife, Millie, headed for the wild west of Colorado, where they became prominent members of pioneer society, raising alfalfa, feeding cattle, and working a large orchard.

- “We are proud of ‘old Wisconsin’ and rejoice in its many success,” Booth told the Wisconsin Alumni Magazine shortly before his death in 1912. “The University of Wisconsin is still serving the people, and may she continue to be so.”

Charles Wakeley 1854, MA1857

- With Booth, he was the other of the first two graduates of the University of Wisconsin. He founded the Wisconsin Alumni Association in 1861.

- Wakeley practiced law in Madison for most of his life and was named Justice of the Peace of Madison in 1884.

- Wakeley was a witness to the assassination of President Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in 1865. As he recounted, he “had a close and clear view of all that took place, heard and located the pistol shot, saw the tragically theatrical pose with the dagger, the stumble in striking down on the stage, breaking the ankle, and heard most distinctly and unmistakably both the exclamation of Booth, ‘Sic semper tyrranis’ and ‘Revenge for the South,’ and the classical, critical observer noted that the criminal blew away the last vestige of dust from his imagined bed of glory by accenting "tyrannis" on the first syllable.” (From the 1893 Biographical Review of Dane County)

Albert U. Wyman

- As a boy, Wyman worked at his father’s newspaper in Madison and was appointed a state printer by the Wisconsin legislature at age 15.

- Wyman did not graduate from the UW, but went on to serve as U.S. Treasurer under two presidents, Ulysses S. Grant and Chester A. Arthur.

- In 1901, he was appointed to the office of the auditor of the War Department in Washington D.C. and worked there until his death at age 81.

Hayden Kellogg Smith MA1867

- Smith served as editor-in-chief of the Milwaukee Sentinel from 1866–1871, then wrote for the Chicago Times, Chicago Herald, and Chicago Chronicle.

- He also lectured on economics at the University of Chicago until 1881 and wrote a book on socialism.

Robert Ream

- The Ream family moved to Washington, D.C., before Robert had the chance to graduate from the UW; he fought in the Civil War and lived the rest of his life in Arkansas, “an adopted citizen of the Choctaw Tribe,” according to his obituary.

- Ream’s sister, Vinnie Ream Hoxie, was an art prodigy, best known for sculpting a statue of Abraham Lincoln that stands in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. She was the first woman, and, at age 18, was the youngest individual at the time to receive a federal art commission.