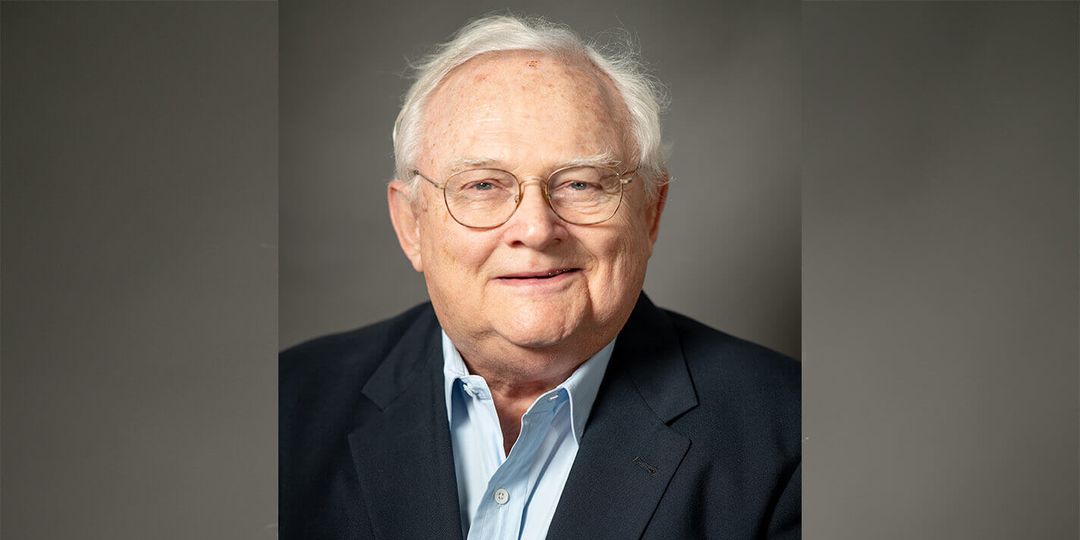

2012 Distinguished Alumni Award Honoree

Ben Sidran's music career began when he played with Steve Miller x'67 and Boz Scaggs x'67 in a band called The Ardells during their UW undergraduate days. Then Sidran wrote the lyrics for Steve Miller's hit song "Space Cowboy," using the proceeds to pay for his PhD in American Studies at the University of Sussex in England.

Sidran went on to produce the music of pop and jazz artists, create jazz programs for radio and television, and record and perform his own music.

Sidran hosted National Public Radio's landmark series Jazz Alive, which won a Peabody Award, and his thirty solo albums include the Grammy-nominated Concert for Garcia Lorca. As a producer, he worked with noted artists including Van Morrison, Diana Ross, and Mose Allison. His soundtrack for the film Hoop Dreams gained acclaim, and his score for the documentary Vietnam: Long Time Coming won both an Aspen Film Festival award and an Emmy. He wrote two books about jazz, Black Talk and Talking Jazz, and a memoir titled A Life in the Music. He recently fulfilled a lifelong goal to record an album of Bob Dylan songs, Dylan Different.

He and his wife Judy '69 moved from the west coast to Madison in 1972 because they missed the Midwest lifestyle. Their son, Leo Sidran '99, has become a national music phenom in his own right.

Sidran has advised the UW Center for Jewish Studies and was involved in a WAA/UW For You tour this past spring as he visited with alumni and promoted his latest book, There was a Fire: Jews, Music and the American Dream.

Jazz holds important insights for Sidran. "If you spend ten years blowing through a copper tube, that copper tube will not be changed. But you will have changed," he says. "When you work on an instrument, you are really working on yourself."

In Appreciation

I am honored to receive the University of Wisconsin Distinguished Alumni Award.

As a young person, my strongest desire was to be respected by the people I respected. The first among them was my father, who was also a graduate of this University, and many of the others I encountered or discovered here in Madison upon arriving in the fall of 1961.

For me, it was like arriving in Oz. I had never known such a flourishing of ideas, people, cultural and political events. I think I grasped immediately that it was OK to be who I was and that my assignment was to figure out who that might be. I had arrived at this feast with a yawning hunger. Each semester we perused the timetable of classes — a vast intellectual menu for the coming months — and on the appointed day, we raced from one end of campus to the other trying to string together the optimum repast. Comparing results at the Memorial Union later that evening was always the beginning of yet another great adventure.

I admit, I never wanted it to end. And as you can see, many decades later, I'm still here at the Memorial Union, comparing notes.

It goes without saying that not all of my best ideas came from the classroom. In fact, my GPA, while nothing to be ashamed of, was not always distinguished. But of course this was back before students became information consumers and we were often just happy to have survived a particularly grueling semester of linguistics, logic or intellectual history. Years later, when I heard about the "Wisconsin Idea," I realized I had lived it. Learning was greatest when it had practical application to one's daily life, and the integration of learning and life is still what carries me forward. The knowledge that this was not only preferable but possible was the greatest gift I received in return for my tuition.

I have to make reference to several professors who had a profound influence on my education. The first was Robert Kimbrough, who was not only a gifted English teacher but also my advisor, and it was Professor Kimbrough who confronted a rather dazed and confused sophomore requesting to withdraw from the University for the semester, a bit after the formal deadline, so that he could go to work full time in a record store. Giving me the room to invent myself — because without the possibility of failure there is no possibility of success — was the gift of Prof. Kimbrough.

The second was Wilmott Ragsdale, who taught Journalism but what he really taught was life. It was Professor Ragsdale who, after listening to a long soliloquy about how the revolution was happening on the streets and naturally one could not always complete one's assignment on time, offered these fateful words, by which I have tried to live ever since: "Ben," he said, "work, don't think."

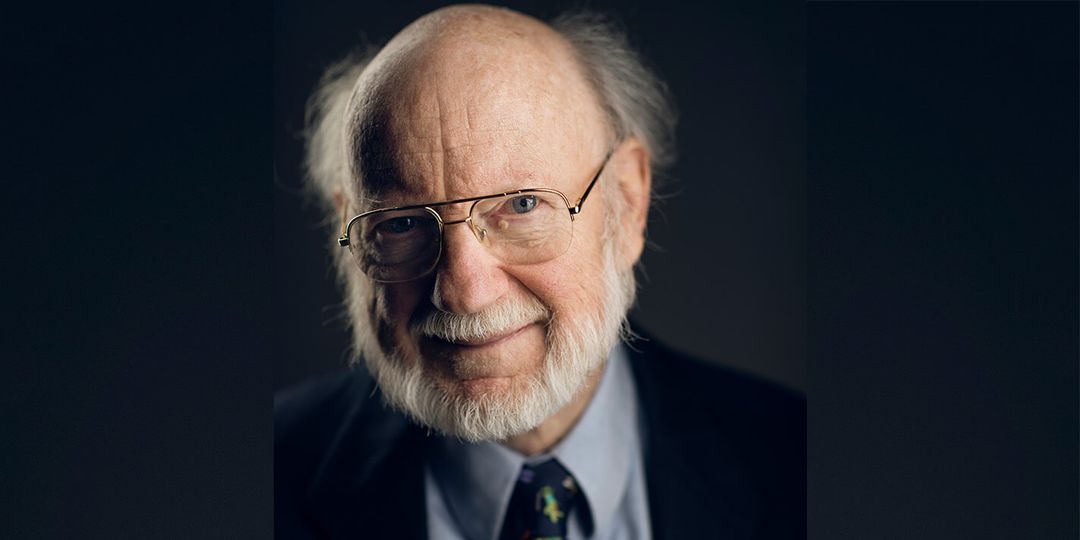

And finally, there was Harvey Goldberg. Much has been said about this revolutionary teacher, scholar, performer and all-around mensch, but simply put, Professor Goldberg gave direction to my life and informed me that this life I was living was every bit as important and strategic as those that we studied in class. He told me, "This is what history feels like!" And he was right.

Neither my father nor Harvey Goldberg is with us any longer, but I carry them within me and I know that this award has made them both very pleased. I can feel it.

Thank you.

Related Links

The Music of Surprise

Earlier this month, we grabbed coffee with the Madison music legend; hear his musings on style, storytelling and the real meaning of jazz.