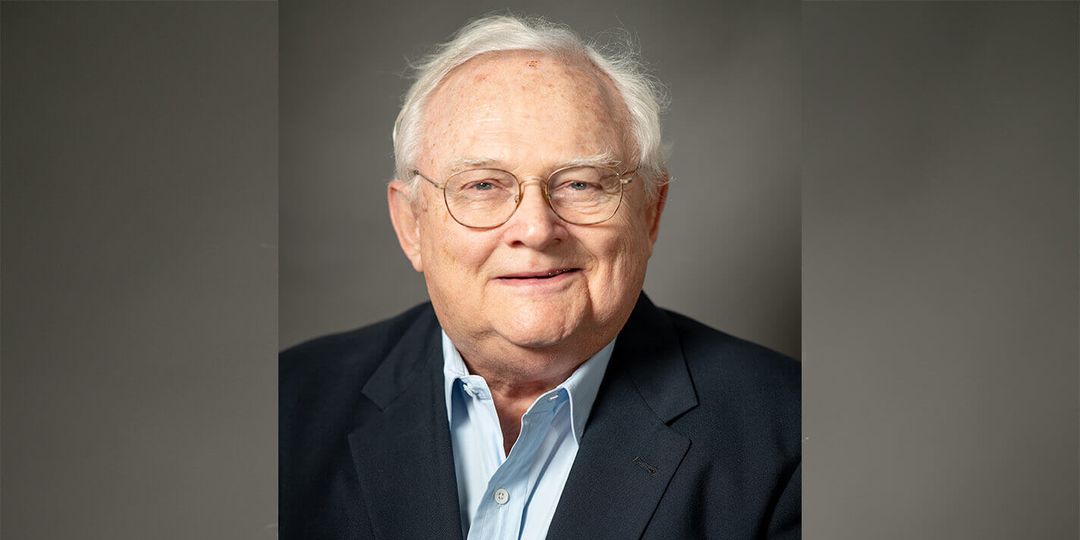

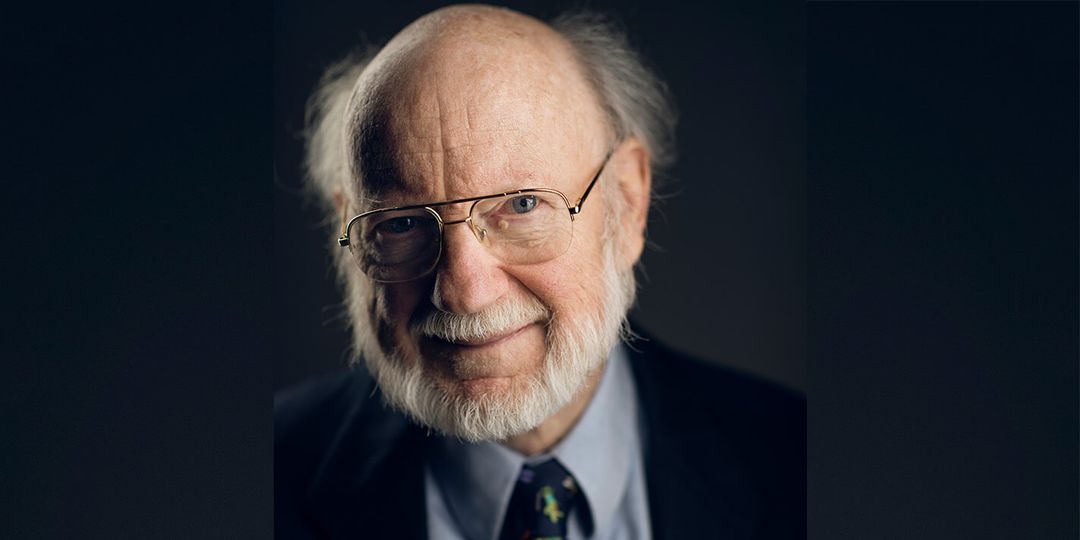

2008 Distinguished Alumni Award Honoree

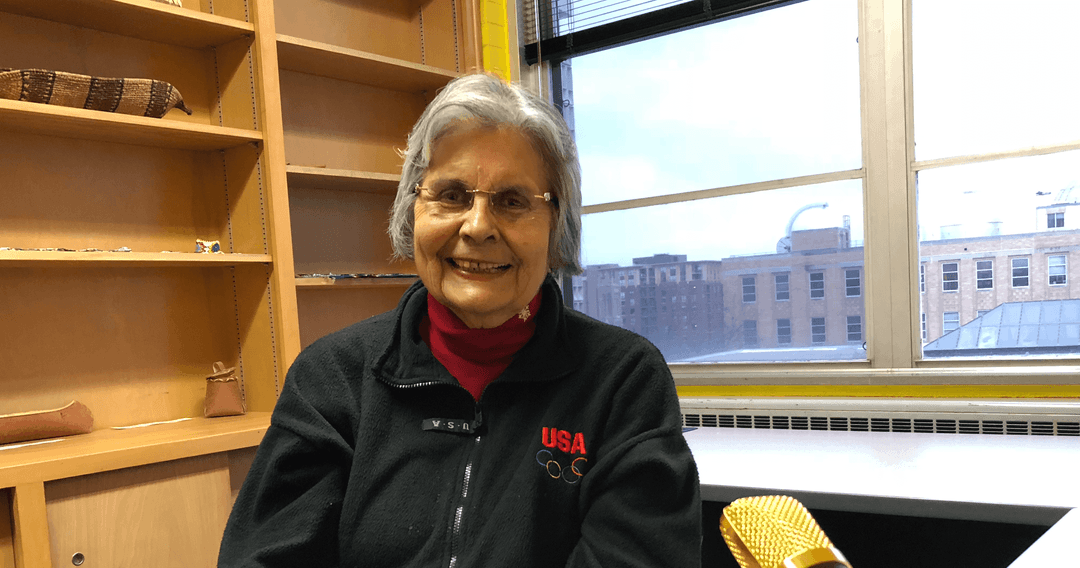

For more than half a century, Sheldon '51, LLB'53 and Marianne x'54 Lubar have worked together to exercise their quiet influence to improve their community, their state, and the nation. Their partnership includes leading efforts that have helped produce innovative programs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and UW-Milwaukee, a nod to their particular love of education. They have both been long time leaders of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

The partnership that defines Sheldon and Marianne Lubars' lives began in a dining hall. And it began badly.

Sheldon was waiting tables in Shoreland House, a private residence hall where Marianne was living as a seventeen-year-old freshman.

"I spotted him on my first day," says Marianne. "I poked the girl next to me and asked who the waiter was. She told me, and I realized I'd heard of Shel from my sister. He and his friends were always pulling pranks - ones that they thought were terribly funny, though the rest of us didn't think so."

But what Sheldon lacked in service skills -- "I was demoted pretty quickly to dishwasher," he says; "I wasn't very good at that, either" -- he evidently made up for with other attractions. The two began dating and married in 1952.

As they tried to establish their family, Shel, a graduate of the School of Commerce, delved into the study of trust and estate law. "I thought my mission in life was as an estate planner," he says. But when he graduated, Marianne was pregnant and jobs were scarce. Even Sheldon's hope of landing a position with the Air Force disappeared in 1953, when the Korean War ended and the armed services saw deep cutbacks.

The Lubars moved to the Milwaukee area, where they'd both grown up - Shel in Whitefish Bay, and Marianne in Kenosha. There Sheldon found work as a banker with Marine National Exchange Bank. "I worked in the trust department for about a year and got bored," he says. "I really thought it was time to leave and find something new."

Instead, in 1958, Marine launched a holding company called Marine Corporation -- the first U.S. bank holding company formed since the Depression -- and Shel took a leading role in arranging venture capital. During his time there, he began devising a theory he called "professional ownership," and now "enterprise development."

"Most companies then were run by owner-operators," he says. "The people who owned them were also the ones in charge of day-to-day operations. By separating these two functions, the company could gain total objectivity."

Over the following years, Shel tested his theory by buying, improving, and selling a series of companies. His reputation as a talented financier led to national recognition. In 1973, the White House appointed him assistant secretary for the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and through the 1970s, he worked under Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter in a variety of economic positions. In the late 1970s, he returned to Milwaukee and set up Lubar & Co., the firm he still heads today. A private investment firm, Lubar & Co. continues to follow Sheldon's theory of professional ownership.

As Lubar & Co. has grown, Sheldon and Marianne have used their earnings to benefit their home city and state. In particular, the couple's aid has reflected Marianne's devotion to reading, the arts and education.

"When I was in the second or third grade," she says, "a school librarian sought me out and handed me a book -- I don't remember exactly what it was, but it was by Rumer Godden, and it was a little advanced for my age. That attention gave me a love of reading that I've had ever since."

Convinced that "libraries are the most democratic institutions we have," Marianne has served on the boards of the Milwaukee Public Library and of UW-Milwaukee's Golda Meir Library. They've aided the Milwaukee Public Museum and the Milwaukee Museum of Art, as well as the Milwaukee Jewish Historical Society.

But the main beneficiaries of their financial aid have been the state's two largest public universities, UW-Madison and UW-Milwaukee. Sheldon has served on the UW Foundation board and spent nine years as a member of the UW System Board of Regents, including a term as the board's president in 1997-98.

"The UW has been a huge influence in my life," says Sheldon. "It's nothing in particular that I learned there -- it was everything about the experience. It made it possible for me to do all the things I've wanted to do."

In Milwaukee, the Lubars made the largest single donation in the university's history, more than $10 million to the school of business administration, now known as the Lubar School of Business. They had previously funded scholarships there, as well as a chair in the subject of free enterprise.

The Lubars have offered even more eclectic support to their alma mater. In 2007, they joined in with several other alumni to fund the Wisconsin Naming Partnership at the Wisconsin School of Business, successor to the School of Commerce where Sheldon earned his first degree. The Lubars offered $5 million of the gift's total $85 million, paid to the school on condition that it not sell its naming rights to any individual or group for at least twenty years. And in 2005, they helped found the Lubar Institute for the Study of Abrahamic Religions, a religious study program that looks at intersections between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

"In the midst of the bitter conflict we've seen in recent years between Muslims, Christians, and Jews, we wanted to facilitate an interchange of ideas among these three great religions," says Sheldon.

The Lubars also raised four children: David, Susan Lubar Solvang, and Joan Lubar, and Kristine Lubar MacDonald MBA'80, and they have eleven grandchildren. And Sheldon still occasionally waits on Marianne's table and washes her dishes -- although, he admits, "not too often."