In 1973, the U.S. National Cancer Institute Advisory Board designated UW–Madison as one of the country’s first six Comprehensive Cancer Centers — comprehensive, meaning that the UW Hospital and Clinics provides excellent treatment, and the university conducts some of the nation’s most promising research. Since then, the center has gone through a few changes (it’s now called the Carbone Cancer Center), but it continues to burnish its image as the place to go if you want to understand or cure cancer.

Howard Bailey joined the Carbone team in 1988, and he’s been the center’s director since 2013. “What struck me about the place was the blending or melding of the art and compassion of taking care of people with technology and innovation that we were applying to the research,” he says. “To this day, we really focus on the emotional needs of our patients and families. But then we also work diligently on, pardon the term, the blood and guts of medications, and new technologies and research.”

Carbone celebrated its 50th anniversary last year, but its history runs deeper. Bailey, who plans to retire in 2024, lists these events as seminal moments in the center’s story.

1940: Harold Rusch ’31, MD’33 (above) seeks funding to create a series of cancer research laboratories, later named the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research. According to Bailey, “he was the godfather of all cancer research and care at this university.”

1942: Mary Lasker x1920 and her husband, Albert, form the Lasker Foundation. “They’re really credited with a lot of the development of the National Cancer Institute as we recognize it today,” Bailey says.

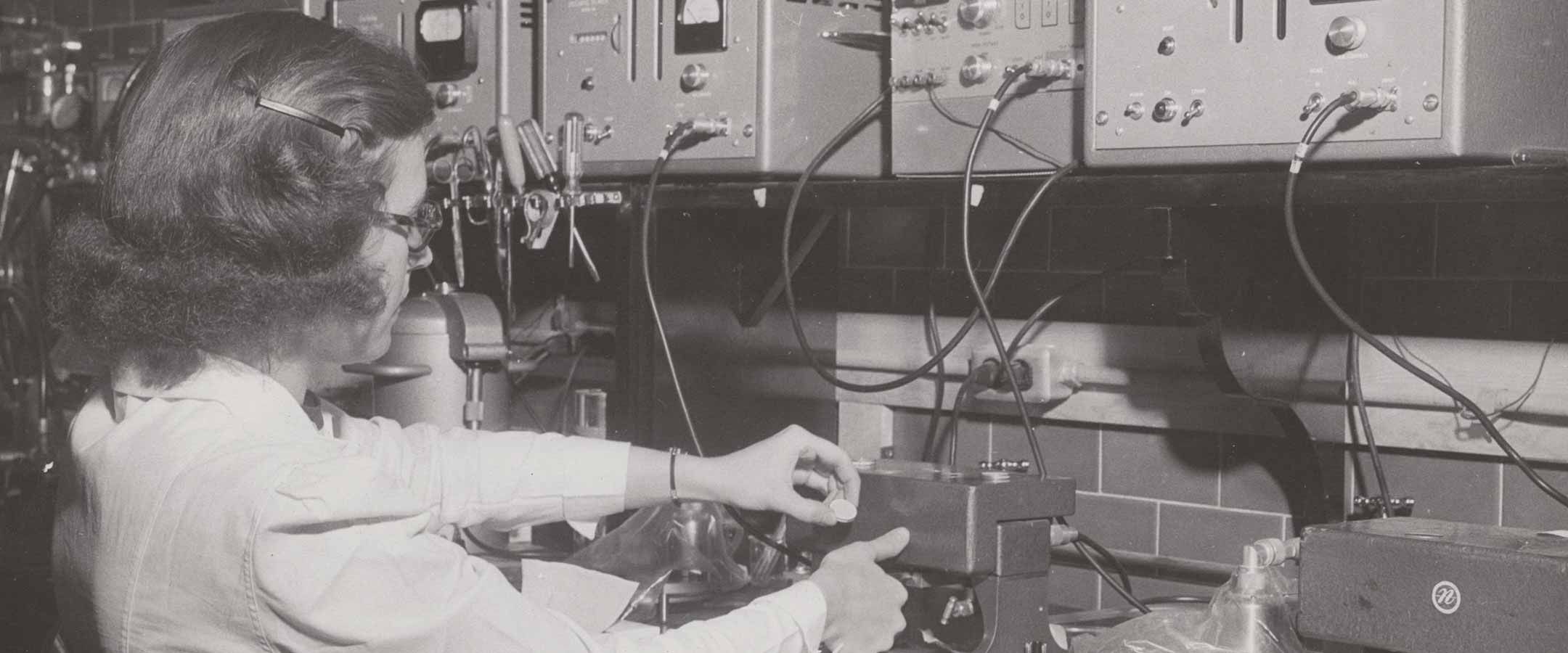

1946: James and Elizabeth Miller join the McArdle Lab’s staff. “Elizabeth and Jim Miller really discovered a lot about how chemicals induce and cause cancers,” Bailey says.

1947: The UW creates the Department of Oncology. “As far as I know, the UW might’ve had the world’s first university-based cancer research department,” Bailey says. “If [previous] cancer-focused areas existed, they were hospital-based; they weren’t university-based.”

1957: Charles Heidelberger publishes a study showing that the chemical 5-Fluorouracil inhibits the growth of cancers, effectively identifying the first successful synthesized anticancer drug. “Charles Heidelberger hypothesized that if you interrupted the development of the genetic building blocks of DNA, that might be an effective anticancer agent,” Bailey says. “It’s still the bedrock [of] any number of anticancer agents today.”

1960: Howard Temin joins the UW staff. According to Bailey, “he discovered, literally, how viruses cause cancer [and] how they specifically, genetically do that.” In 1975, Temin won a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work.

1973: The National Cancer Institute designates UW–Madison as a Comprehensive Cancer Center, and in 1978, Paul Carbone is named its director. “He codeveloped curative therapy for what’s called Hodgkin’s disease,” Bailey says. “Before [Carbone], people just cut a tumor out and hoped the cancer didn’t show up again. What Paul Carbone invented was adjuvant therapy, the concept of giving chemotherapy [along with surgery].”

1980: V. Craig Jordan ScD’20 joins the staff. “He worked with tamoxifen, which was initially being developed as a sheep fertility agent,” says Bailey. “He looked into this and discovered that it was an effective anticancer agent for breast cancer.”

1993: Rock Mackie publishes his discoveries about TomoTherapy. “Carbone has a legacy of great discovery,” Bailey says, “but that, in itself, isn’t enough. It’s our legacy of great discovery applied to our patients and their families.”