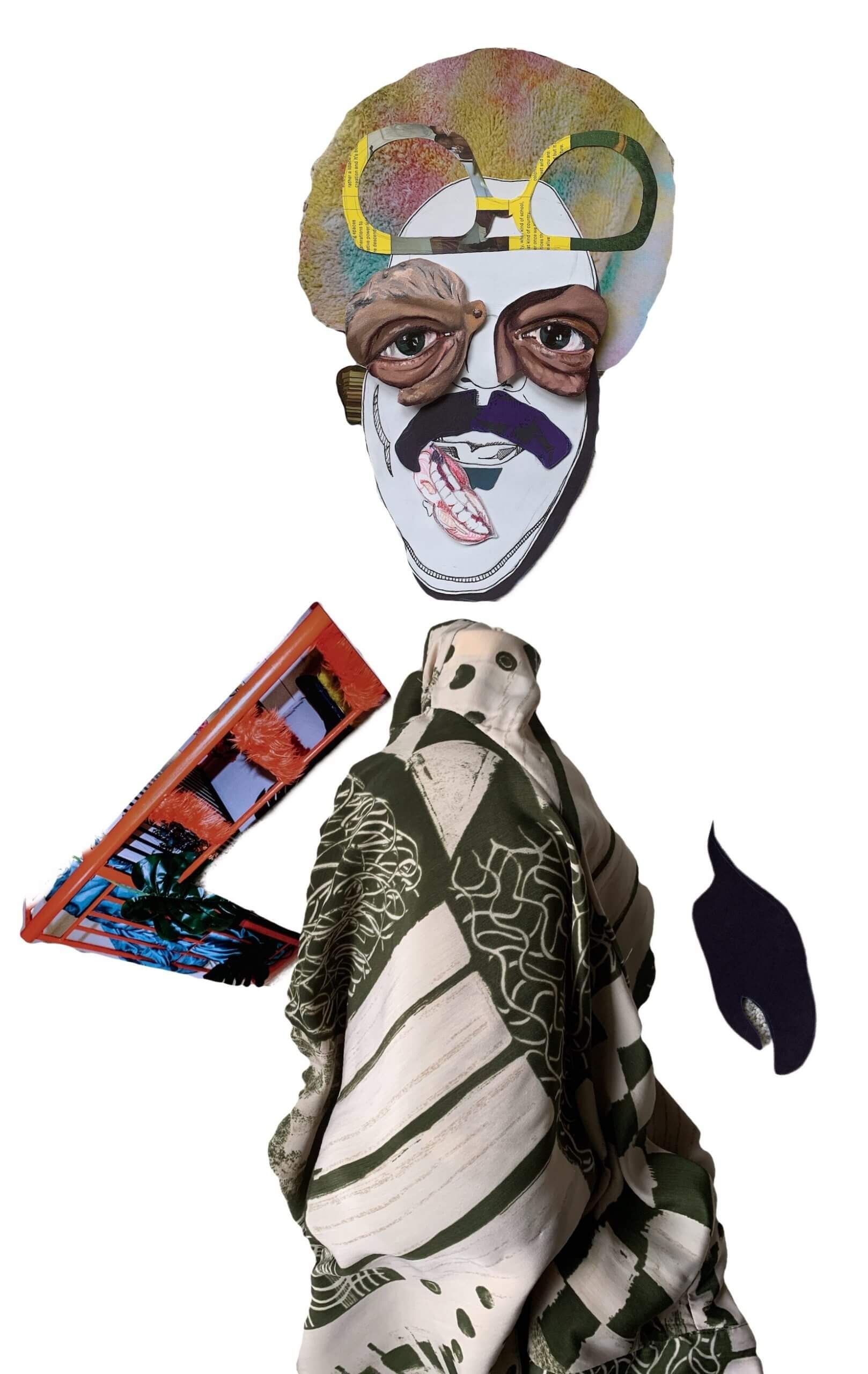

Shiloah Coley ’20 is changing the world one brushstroke at a time. An artist whose practice focuses on oil painting and wooden collages that explore notions of Black identity, Coley has taken her talent everywhere from Rio de Janeiro to Johannesburg, from Brown University to New York City, and back to Madison this summer to paint a mural on State Street. Now, this artistic Badger is headed to Washington, DC, to pursue her MFA, but not without her signature critical eye for equity in the art world. A Truman, McNair, and Posse scholar whose passions lie in both creating art and studying its role in and impact on communities, Coley is committed to breaking down the barriers between artistic spaces and practices and the people who need them most.

What role does art play in your life?

I think that art’s becoming for me what it was when I was very small: art was always very liberating for me. As someone who was an only child and very much so in their head a lot, I always found art to be an avenue for expressing myself and getting it out, whatever was in my head. Over time, as people view your art and critique your work, I think you become much more concerned about outside perspectives and interpretations, and I think that’s what I started to feel in high school is more pressure to make it look perfect. It wasn’t until my junior year here at UW that I [talked with a professor about] how art should be a liberating thing for the artist; you shouldn’t feel like you’re held under these certain constraints all the time, or you shouldn’t be feeling like you have to make a certain type of work for people. It should come from within you. I also am just of the mind-set that, especially when we are talking about Black artists or other folks of color, sometimes people expect those people to make certain kinds of art, but I think if we’re really talking about a radical liberation, they should be allowed to make whatever art they want to make that’s liberating for them.

Why did you feel called to contribute to the State Street mural project?

As someone who just graduated from UW, there wasn’t really a ton of closure, I think, for a lot of graduates and their time here. And Madison was definitely never a place I envisioned living in. It took three years for Madison to grow on me. I genuinely would say it wasn’t until my senior year that Madison started to grow on me. But something I can genuinely say is I had such an incredible community of folks, scholars, community members, friends who’ve really nurtured me here over the course of the past four years, and I think I really viewed it as an opportunity to give back to a place. I’m really grateful for the growth that I did here. Even if a lot of it or some of it might have been painful, and might have been hard, I wouldn’t trade it to have gone any place else.

Can you tell me about some of the research you’ve done?

Something that really got me in Rio was that there’s graffiti art everywhere in Rio, and it’s really not criminalized, for the most part. It’s literally everywhere, and it’s something that the city is very known for at this point. And it made me curious about knowing the history of graffiti art in the U.S. So when I was doing research on the beginnings of graffiti art in the U.S., what I learned was that it was largely birthed out of the hip-hop movement in New York and predominantly Black and Latinx youth seeing graffiti as a way to reclaim space in the city as New York started to be gentrified. But as more upper-class white folks were moving into the city, as we know, Black and Brown folks get pushed out, and a lot of youth saw it as a way to actively reclaim space and be like, no, this is our territory. And [while] a lot of people tie graffiti art to gang violence, and while there are gangs that participate in graffiti, graffiti also has a culture of its own. There are graffiti artists and crews that are totally separate from any connection to gangs, and it was just a way for them to be like, “Yo, we’re still here.” And I think in knowing that history, it really challenges our framework from which we think about the criminalization of graffiti art, because it’s like, oh, this is a group of youth trying to get a city to listen to them, and because their voices are actively being silenced, this is what the product is.

Do you have any ideas for what your artistic work or research is going to look like going forward?

A piece of my work that I was starting to work on in the advanced paint workshop at UW — that never got fully finished because of COVID — is magnetizing my collages so that people can actually manipulate them: essentially, having the wood pieces have magnets behind them and then having the viewer be able to pick them up and move them around on the actual surface. I’m really more interested in public art projects than I am showing in galleries, even though at the end of the day, sometimes you do have to do what makes money just to survive. So I will show work in galleries, but my preferred showing arena is either public spaces or just community spaces, because I want people to be able to freely interact and engage with the work. And I think part of my own mini personal protest to gallery spaces is a lot of gallery spaces will tell you [that] you can’t touch the work. And I want people to have to touch my work. I want them to have to move it around and be a part of the art, if that makes sense, as opposed to creating this barrier between the work and the people or the community.

What has been your most moving or influential moment as an artist?

Someone I know messaged me on Instagram, and she basically was like, “Yo, I just want you to know your piece really moved me.” This is a Black woman who told me this. She was like, “I stood there and I almost started crying looking at it, and I just want you to know that your talent is really beautiful and your work has the power to really move people. It’s really clear that there’s a purpose for you in art.” And for me, something I’ve always carried as a Black woman who’s an artist is feeling a lot of pressure like I wasn’t doing enough for the community, like my work wasn’t purposeful enough. Like, yes I’m a visual artist, but how do I engage with the community beyond that? And I think that’s why I’ve been invested in art programming, and research, and that kind of stuff beyond just being a visual artist. And I think to hear someone tell me like, “Yo, your visual work is enough,” that meant a lot to me. It really moved me because I’ve never really audibly heard someone say, “If this is all you do, this is enough.” And I think that meant a lot.

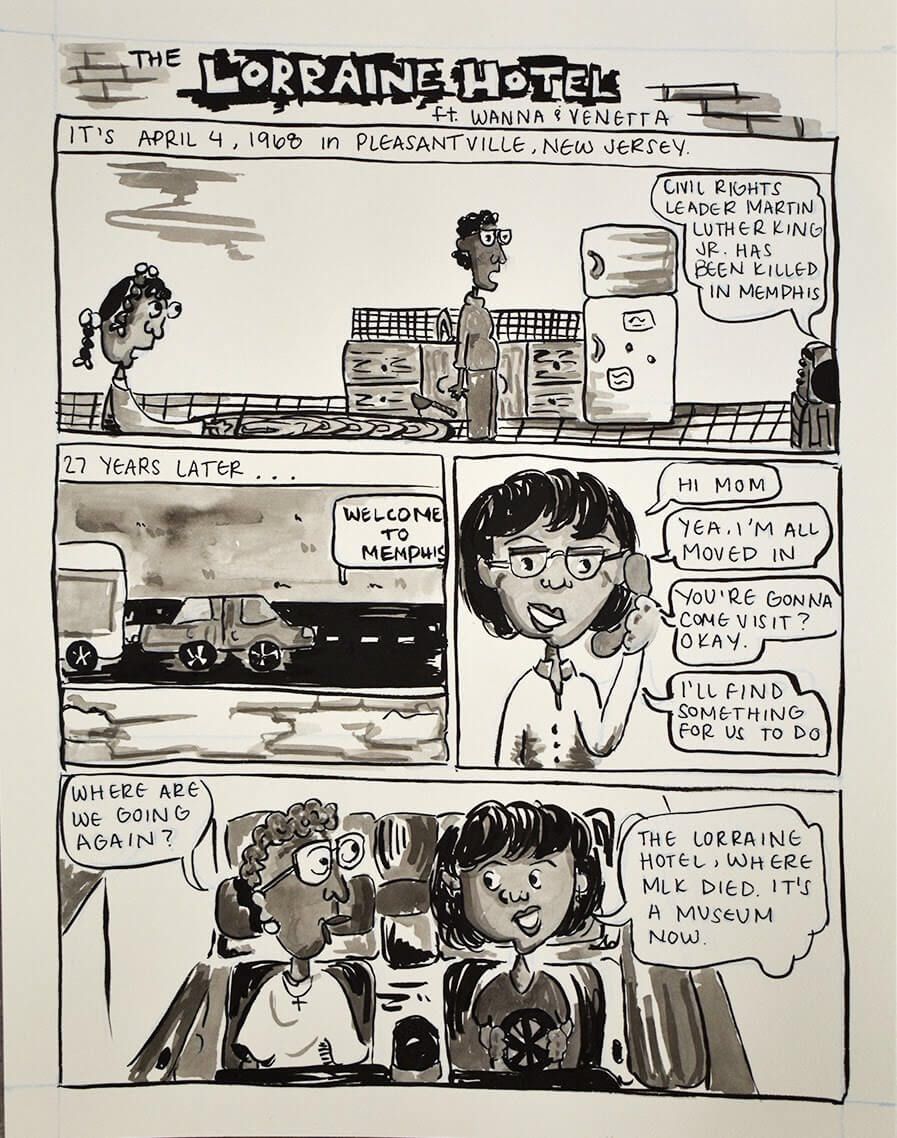

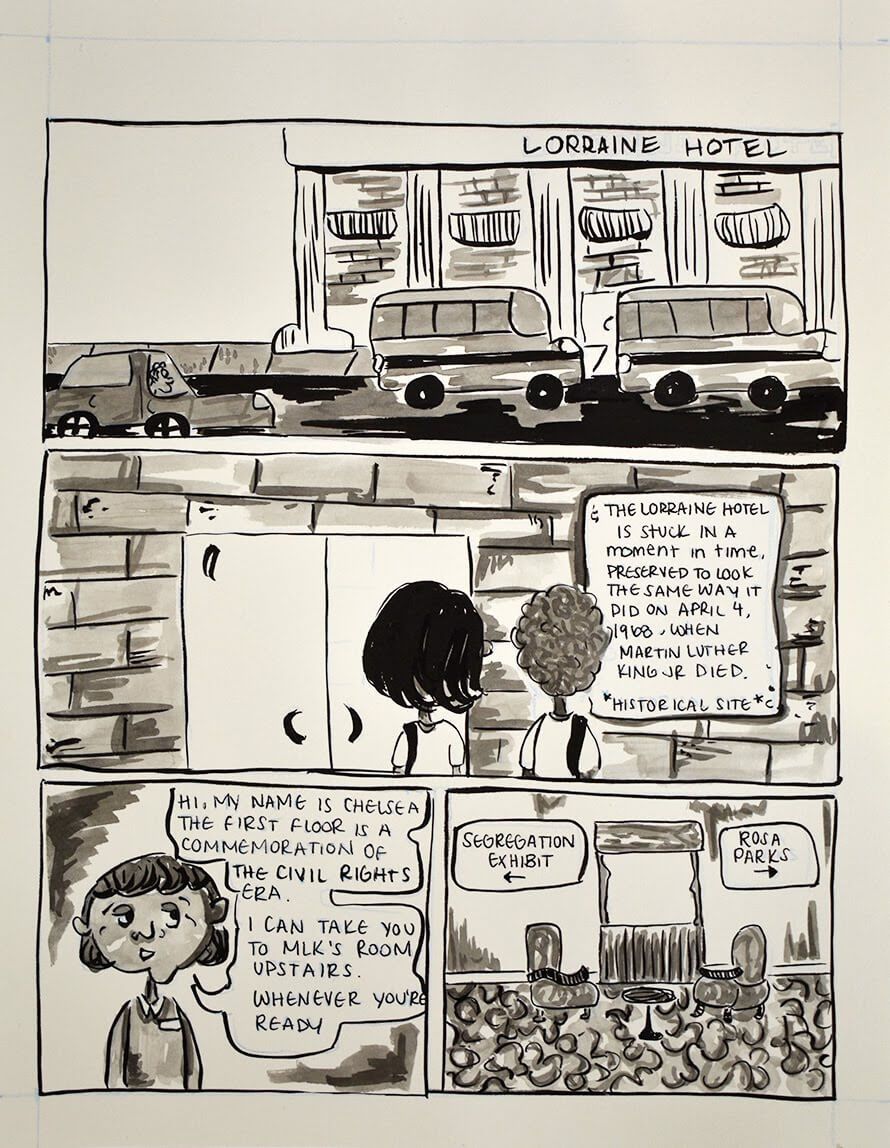

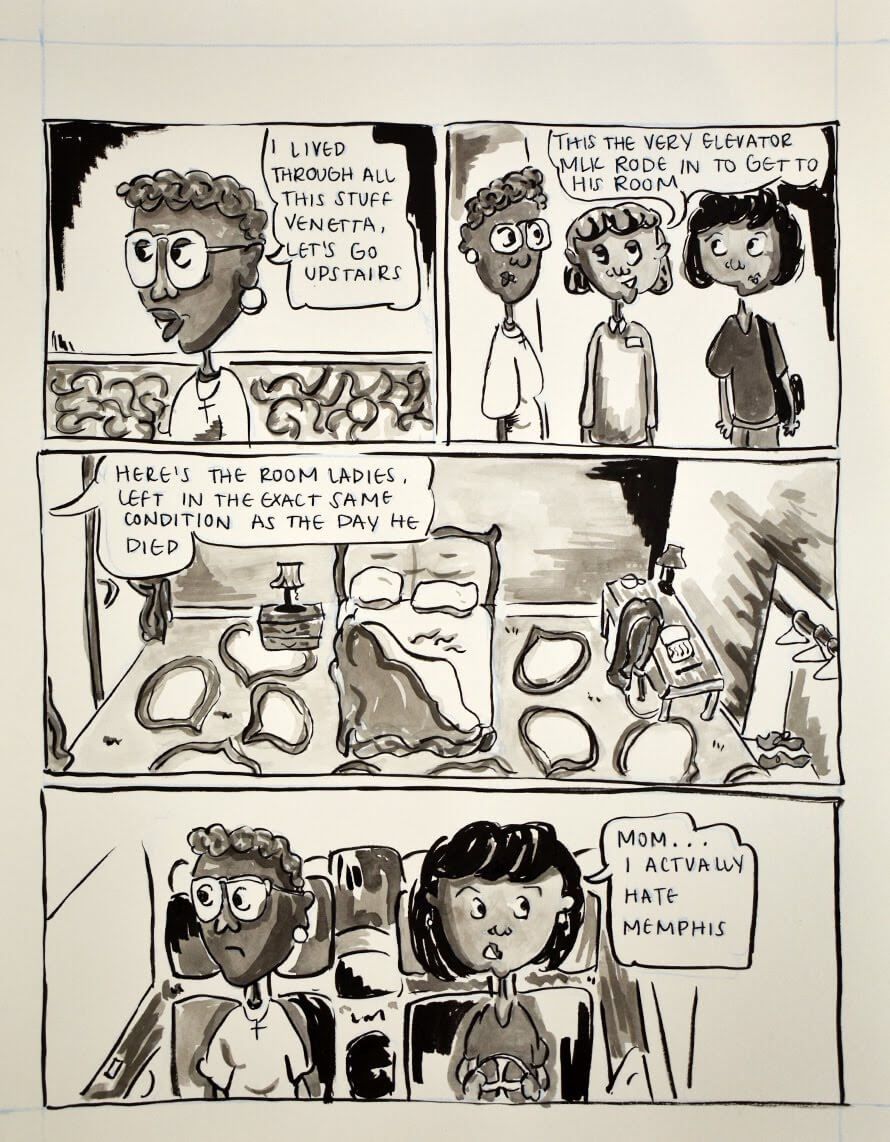

I also understand that you draw comics. What artistic purpose do those serve in your practice?

I say community work feeds my artistic practice and my artistic practice feeds my community work, but I think the comics, I’d say are the most selfish of all of my art. And I’d say it’s because it’s definitely more grounded in the development of my own sense of narrative and how I understand my relation to my family and my community and my own identity. I think the comics are more of like a self-exploration of better understanding myself, to be quite honest. I had never really been forced to confront my own Blackness until I got to UW. For a lot of people, that’s like the first thing they see and that’s something I have to figure out. I wasn’t aware of my Blackness playing such a crucial role in my identity until I was at UW. I think that comics just really allowed me to explore, not even my experience at UW, but it was really me just making sense of my own childhood and upbringing and intergenerational Black womanhood. I was very much so raised by my grandmother and my mother, and thinking about the things I’ve learned from them in the time I’d spent with them. So, I’d say my comics are definitely the most selfish in regards to the work I make, and it’s really just me thinking about my own stories and the history of my own family and developing my own sense of narrative in regards to awareness surrounding myself and my placement in the world and my identity.

That’s an interesting use of the word “selfish.” Why do you use that word to describe this part of your practice?

Why you hear me use the word “selfish” is because for me, for so long, that studio practice did feel selfish in comparison to all of the work and improvement that I think needs to be made in my world and how the arts can be utilized to do that. So, I think for me you hear the word selfish because I still struggle to find a balance between making work with and for the community as opposed to work that is definitely more autobiographical and more about my own story.

You wanted to double major in studio art and journalism, but the university didn’t offer that option. What new opportunities opened up — maybe that you had never considered for yourself before — once you settled on a journalism major and studio art certificate?

I thought to myself, “What other avenues can I use to pursue what I’m interested in in regards to the arts and community work?” And I think that’s what really has inspired the community engagement type of work I started doing in Madison. So, I think right after I found out I couldn’t double major in journalism and studio art, I ended up applying for an internship with the Madison Children’s Museum which revolutionized the way that I perceive the role that the arts could have in community building and cultural connections and that kind of stuff, because it was a joint internship between the Madison Children’s Museum and Play Africa, which is a children’s museum in South Africa. My main task was creating a program that could facilitate cultural exchange between the children in Johannesburg and Madison without them ever meeting, and I immediately was like, “Oh, I could definitely do that through an art program.” And then everything cascaded from there, because then when I was in Johannesburg, South Africa, with Play Africa, I had the opportunity to work with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. So, I guess the short answer is that because I felt like I couldn’t get what I needed from the university in that moment, [it was] time for me to look elsewhere for how to do the work that I want to do outside of the classroom. I realized that there was a market for me to be able to combine all of my passions — working with the community, and using art as a tool and a resource, and maintaining my own studio practice — that there was space for that. I just had to create those opportunities as I moved along.

Tell me more about your time in Johannesburg.

[The Madison Children’s Museum] wanted someone to facilitate a program that would foster a cultural exchange between kids in Madison and Johannesburg. I was able to travel, but obviously the kids couldn’t, so what I did was I designed the “This Is How We Do It” program where kids made art about their daily lives. So, in Madison, I ran the program and kids responded to prompts like “This is what I wear to school,” “This is who I live with,” “This is my favorite toy,” and they would make art about it and then write a short sentence or two underneath it. And what happened is all of the work of the kids in Madison then went with me to Johannesburg when I went to Play Africa, and the kids there got to see what the kids at Madison had done, and the kids in Johannesburg essentially responded to the same prompts. It was just cool to see the kids and adults didn’t even recognize [that] there’s way more similarities amongst kids across the world than there are differences.

While I was working at Play Africa, I was essentially the art programming intern, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art reached out to the CEO [of Play Africa] about them running a #MetKids program, which is where kids make art based off of the Met’s archives around a certain theme, and they asked Play Africa if they wanted to be involved in this. The CEO approached me and she was like, “Hey, we have this opportunity to work with the Met. Do you mind taking over this project coming up with your own idea for what you want to do?” And I remember being so surprised. I think I was going into my junior year, so I very much still felt like a little baby in college. And I was like, “Okay, yeah, I can email the Met. I can do this.”

I really [wanted] the theme of this project to be kids at play [and] kids with their families. I want kids to feel empowered in making this work and have it be about kids and portraits of kids and that kind of stuff. So, I’m looking through the Met’s archives and I realized there’s no representation of children of color whatsoever, and I’m not going to have these kids just re-create images of white families. The demographic I was working with was predominantly Black children, [and] I can’t have these kids just re-create images of white European families. I scrolled through like 1,500 images of their archives, and I found, like, one image of a Black child or a Black teenager, and the rest were just renderings from slavery or field work, and I was like, “Okay, no, that’s not what I want to do.” So, I contacted the Met and I was like, “Hey, I want to change the program. I don’t want these kids to just re-create the images they see in these pieces. What I want them to do is re-create it, but make it representative of their own lived experiences, their own lives and their own dreams.”

I had [the kids] look at the compositions of the different families — portraits of families and children at play or interacting with each other, children who are dancers — but I had them re-create it in their own mind-set and make it representative of their own stories, their own livelihoods, of their own families, and it ended up being really beautiful. I felt it was empowering for the kids to have the opportunity to share. The idea was for them to have control over their own narrative and sharing some of their own story.

How did your work continue with the Met?

The program ended up being run really successfully at Play Africa. [Then the Met said,] “We would like to rerun this program at our World Culture Festival at the Met,” which would have been in October of 2018. And I was like, oh, okay. Super great. That’s cool. But they didn’t want me to run it. They were just going to run it on their own, even though I had come up with the idea and redesigned the project. They’re like, “We’ll send you the lesson plan to review. Tell us if it looks accurate, and then we will do it at our World Culture Festival in October.” And I’m super fortunate [because] my supervisor at the Madison Children’s Museum and the whole team there really pushed me to be like, “No, [I] should get to run the program if [I’m] the one who designed it and re-created it and had it be successful.” So, when I contacted the Met about running the program at their World Culture Festival, they were like, “Oh, we would love to have you if you happen to be in New York during that time.” So, basically, that was their way of saying, “Oh, you can definitely run it, but we’re not going to pay for you to come here.” And what ended up happening was I had folks tell me, “You should just email everyone and anyone who you think might have extra money in their pockets at the university.” What ended up happening was the International Internship Program, who had facilitated me going to Play Africa and Johannesburg, ended up paying for me to be able to fly out to New York and stay in New York for a night to run the program at the World Culture Festival.

Did that experience change or influence what you wanted to do with your studies, your research, or your art going forward?

I think after that is when I officially added my [Afro-American Studies] certificate, which is something that I had been thinking about, but I hadn’t done yet. I think part of it was [that] I just realized that I didn’t have to be a one-trick pony, that I could bring my full self to the work that I was doing and that it was valuable and important. Me being able to have that conversation with the Met, like, "Yo, I’m not going to have all these Black and Brown kids just re-create images of white families," that comes from my own lived experience and identity, but it also, I think it’s also important for me if I’m doing that kind of work and hoping to help uplift the voices of the marginalized and oppressed in art spaces.

Something else that inspired what I did was, when I worked with Madison Children’s Museum, Play Africa, and then the Met, I gained more insight on what the nonprofit sector looked like. I really wanted to do research with Black and Brown communities — specifically urban, low-income Black and Brown communities — on how they utilize the arts and how the arts can better be used to support them, and also how arts are already being used in those communities, whether it be as a means of healing, as a means of education, as a means of just self-liberation, how art is used in those communities to do like informal art practices through community art, through graffiti art and street art, and that kind of stuff.

I ended up applying to be an undergraduate research assistant at Brown University in their anthropology department, and I worked with a professor there the following summer. Essentially, I supported her in her project, which was looking at incarcerated Black youth and their access to the arts and the role of the arts as a liberatory practice with Black youth. I did literature reviews and background, looking at what had already been published around the topic, and then I also did the preliminary research for my own project that I was interested in, which was on specifically Black youth and the use of graffiti art to reclaim spaces in major cities.

So, yeah, the long answer is [that] having the opportunity to really combine a lot of my passions and do that important work in Madison and in Johannesburg inspired me to be like, “Okay, now I know what the nonprofit sector looks like,” and [then] trying to navigate [whether I am] more valuable on the ground in the nonprofit sector, or do I really want to focus on the research side of things and hopefully be able to collect data and information that will maybe lead to policy change in how we approach art education or how we look at things like graffiti art and decriminalizing graffiti art and street art?

What are some of your findings from your own research projects?

When I was applying to the Truman Scholarship, we had to write a policy proposal, and my policy proposal was on using arts education with incarcerated youth and the importance of using arts education with incarcerated youth. Essentially, there’s a lot of research that shows that arts education or the arts play a key role in cognitive development, and a lot of Black and Brown youth who are incarcerated, when you look at testing and their cognitive development levels, their cognitive development is not where it needs to be in comparison to where their white peers are. And some people would use that [to say that] Black and Brown kids are just dumb, and it’s like, no, there’s a lot of historical oppressions at work in that. Something that I immediately see as someone who knows that art plays a role in improving cognitive development is like, okay, so then why is art the first thing we take out of schools? Especially when we look at low-income Black and Brown communities, and art being the first thing that’s often cut from public school programs. [If] that’s one of the immediate answers to helping improve cognitive development, why is that the first thing we’re taking out? I believe that the arts should be a part of the core curriculum in all public school systems, but especially in systems where incarcerated youth or at-risk youth are involved.

I had [also] done a project when I was a part of the Global Gateways program after my freshman year of college. In the summer of 2017, I was in the Global Gateways cohort that went to Rio de Janeiro [Brazil], and we took two classes: International Relations from a Brazilian Perspective, and then we did Brazil in Black and White, which was looking at the history of race in Brazil. For that class, we had to do our own mini research project. It could be on anything in the community in Rio, and what I did mine on was, there’s a part of Rio that’s called Little Africa, and it’s a poor area where the slave ships used to dock, but now it’s kind of like this cultural hub for some of the history of slavery and the history of enslaved Black folks in Rio, and they’ve started to do more work in acknowledging that this used to be where the slave ships would dock. While we were in Little Africa, we’d taken an educational tour of the area and we passed a series of murals that were essentially done by local graffiti artists, and the murals were about the history of slavery in Brazil. And what’s this irony is that where the slave ships used to dock is now where cruise ships dock, and [the artists’] goal was to really be able to educate tourists [that] the way Brazil’s portrayed on TV isn’t the way it really is. It’s something like 80 percent of Brazilians have Black in their blood, and [for those artists] it’s really important that when tourists are entering this country, that they’re aware of the history of Black and Brown folks in Brazil, especially those who are direct descendants of the African slavery that ran so rampantly here.

I was able to get in contact with most of the graffiti artists who worked on the project, but I did not speak Portuguese. I do not at all barely speak Spanish, but my professor was fluent in Portuguese and there was another student on the trip who was fluent in Portuguese, and they served as translators for me in being able to interact and interview these artists about their role in this project, what their goal was and being able to educate the larger community who were also uplifting the stories of Black Brazilians and acknowledging the history and re-creating the narrative and the dialogue and acknowledging it around Black Brazilians.

Do you find that your research or goals grapple with gatekeeping or determination of legitimacy in academic and artistic spaces?

I think it is a critique in thinking about where money is being invested in our communities and arts institutions, and what sorts of organizations have access to resources and what sorts of organizations don’t. Another thing that I thought about when you said "gatekeeping" is part of why I studied journalism: I became a little put off by the idea of this thing called “parachuting in” where [researchers] go into these communities, they extract all this information, they use super elite academic language to talk about what they experienced there, and then that information just circulates in academic communities, and undergraduates might read a paper or a book about it and that’s it. That’s really disconcerting for me as someone who’s like, okay, but how did the community benefit from the work you did there? Were there any actionable items that allowed the community to benefit from the research you were doing? [Did you] even attempt to put the work you did into accessible enough language for the community to understand that and have a better grasp of the actual data and what’s going on in their space? Because the community knows what’s going on. They’re already aware of what’s taking place in their own communities, and it just feels like there’s something very wrong about elite academic institutions being able to send in researchers to collect this data, extract it, and even profit off of it without the community seeing anything. So, another thing that I was interested in is how academics are communicating their work back to the communities they engaged with and how we actively make sure it’s a mutually beneficial relationship, which is a big question that I think academics are still facing. I was also interested in how journalism fosters relationships with communities. I think it’s important to talk about doing research with communities and not on communities. How do I make sure it’s a mutually beneficial relationship?

Do you think you’ve found a middle ground or career that encompasses all or many of the things you want to pursue?

That is a question I ask myself every day. At one point, I wasn’t even thinking about doing my MFA. I was like, I want to go get my PhD in sociology and do this research because this is super important. It’s a huge gap in the literature, not that many people are talking about that, not that many people are writing about it, and after being at Brown, doing that type of research and where it was super interesting, I learned a ton. [But I still wondered] do I do better sitting behind a desk, doing all this work, which I’m good at and can do, [or] am I just more well-suited for being on the ground and actually being present in those spaces as opposed to being the one doing research on that work? Or is there a middle ground? I think the answer to that question is, I don’t know. But after I was at Brown, I was like, yo, I want to go do my MFA, especially since I didn’t major in art at UW. I want to really be able to focus on my artistic practice and figuring out what the balance is behind being a studio artist and doing community work.

So that’s a long way of saying I have no idea where I will end up. I think that recently on a job application, I had to answer the question, what do I see as the end goal for my career? And I was really honestly like, I don’t know, but I can give you a couple of things that really interest me:

One of them is potentially being a curator at a history or art museum. Another thing is being a community engagement specialist and fostering this relationship between art museums and the community, because I do think there’s a large gap there in the lack of access that communities have to museums that are located so close to them. I think there’s a huge gap there, that not enough is being done to facilitate a relationship between the two, and I think museums have a duty to be more engaged with the communities, especially the low income and marginalized communities in major cities that are so often just bordering their museums. I was recently applying for a job at an art museum, and one of the questions they asked is how [museums] can better get more marginalized folks in the doors. One of the questions that immediately came to my head was like, “Oh, well, do you ask the community what they would like to see collected?” Like, what would people in the community actually like to see be shown in the space, and is the work being shown reflective of the demographics of the neighborhoods at all? It’s not always physical barriers [that keep people out of museums]. Sometimes it’s literally just how these historic houses of elite institutional thought are so elitist to a certain extent that these walls exist that aren’t even physical walls, but these barriers that the surrounding communities are like, “Oh yeah, that place isn’t for me, or, I didn’t even know what that was or that that was there.”

And then I guess the third one would be, do I want to get my PhD, and do I want to teach? Do I want to remain in the academic setting? But I’d say if I had an idea of an end goal or like three jobs that would in some way allow me to accomplish or combine the passions I have and the work I’ve done, I guess I’d say it would be those three.