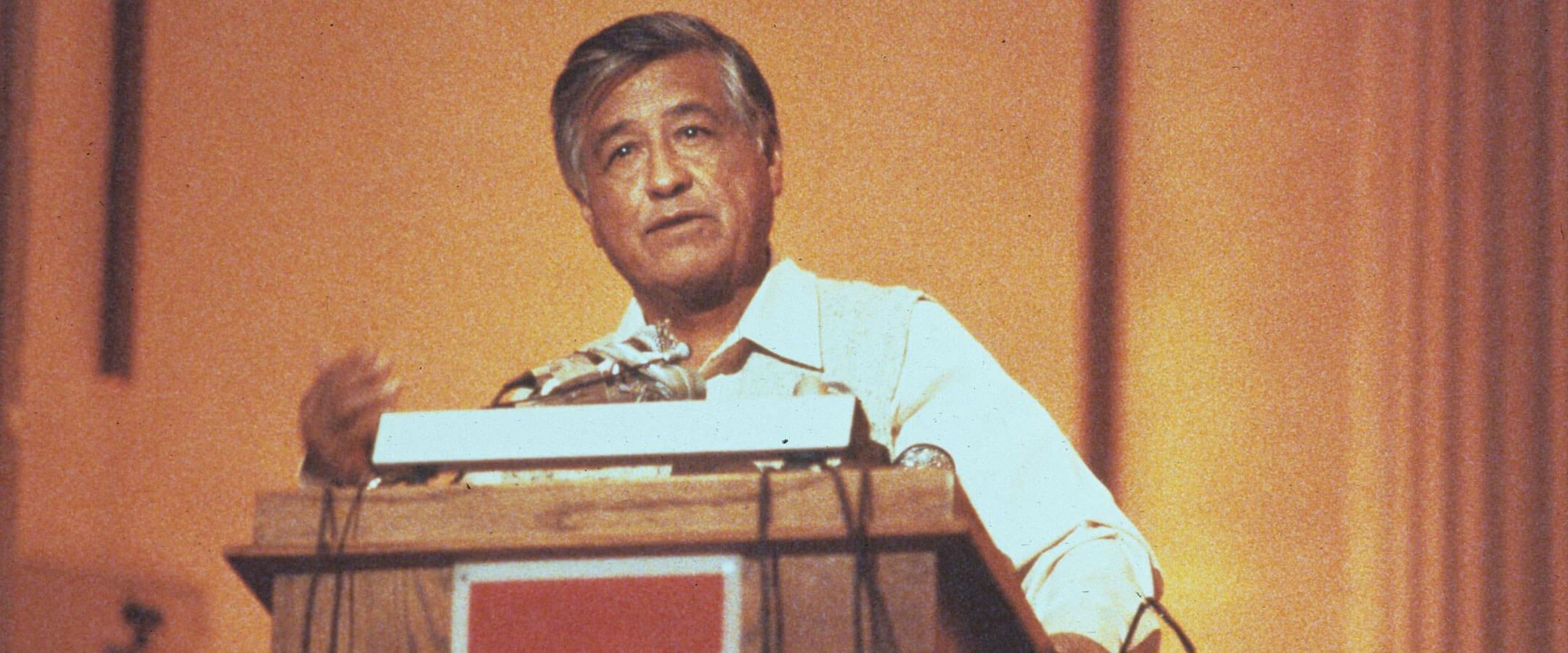

A member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Nicole Soulier ’09, MS’15, PhD’24 has been interested in building a strong community of Native and Indigenous Badgers since she was an undergraduate at UW–Madison. She added a certificate in American Indian studies to her bachelor’s degree in human development and family studies, all while participating in Wunk Sheek, Associated Students of Madison, and the Multicultural Student Association.

When it was Soulier’s turn to share her postgraduation plans at the All-City American Indian and Alaska Native Graduation ceremony, she made a joke that turned into a job. “I tried to be funny about it and said, ‘I don’t have any plans. I don’t have a job, so if anyone out there has a job for me … ’ and I gave out my personal information.” The following Monday, she was working for Madison College as a clerical tech.

The role inspired an appreciation for community college and a passion for education. Soulier returned to the UW part-time to get a master’s degree and doctorate in educational leadership and policy analysis. She still works at Madison College as the director of college access and experience programs, where she supports historically underserved students. And as president of the Wisconsin Alumni Association (WAA): Cooweeja Native and Indigenous Affinity Group, she spends her free time working to welcome current students and new graduates into the Badger community.

How have things changed for current students compared to your time as an undergrad?

What I’ve seen since my time as an undergrad is more of an institutionalization of relationship building. When I was [on campus], we did not have a tribal liaison or a director of tribal relations as we do now. The establishment of that office is really important for students in helping to bridge the university to the communities that those students come from. And that’s a very important part of the student experience on campus because then [the students] don’t feel like they’re stepping away into another world. [They can feel] that the institution itself is not just working on the student but building that relationship with their tribal communities. That’s a great addition: for the university to make that investment in serving Indigenous people and strategizing around how they can better serve our students.

On the flip side, it’s troubling that our students are still trying to validate and justify their presence on campus, and that is evident through the possibility of losing their space over on Mills Street. My dream is that our Indigenous and Native students will have a place that they can call home. They have a house right now, which is over on Mills, but I know that there have been conversations about the future of that space as the university works through some facility planning. My hope is that students don’t have to fight for that because I feel like that’s been an ongoing struggle.

There was an affinity group for Native and Indigenous alumni in the 1990s, and you helped to reestablish the current group in 2020. What made you say yes to this endeavor?

I think it was the value in our community and the service toward our community — knowing that this group, by reestablishing, would have the ability to impact and continue our involvement with the university.

What are your goals for the group?

Right now, we’re still trying to build our base. [Our board is] talking about our recruitment plan for the summer and getting folks who we’ve engaged with over the last couple of years signed on. [We hope to] populate some of our committees so that we can build a stronger network of alumni who are working and volunteering for our organization.

What sorts of events do you organize?

This last semester, we really focused on collaborating with Indigenous student groups and Indigenous-facing organizations on campus. This last spring, we helped celebrate new alumni by cosponsoring the All-City American Indian [and Alaska Native] Graduation. We also helped cosponsor an alumni dinner that was hosted by Wunk Sheek, which is the American Indian student organization on campus. We also played a role in helping with the Coming Together [of] People’s Conference, hosted by the Indigenous Law Student Association. In years past, we did a comedy show with Native and Indigenous comedians during Homecoming.

Why is this collaboration with other groups important to the Cooweeja board?

It’s important for us in terms of WAA’s mission and advocacy that we understand what our current Native and Indigenous students experience on campus. Those aren’t things that we can just learn by picking up a paper or reading about. I think a lot of those sentiments come from a shared, trusted relationship. So, it’s important for us to be a partner and to be involved with the current students on campus and to let them know that we are here to support them.