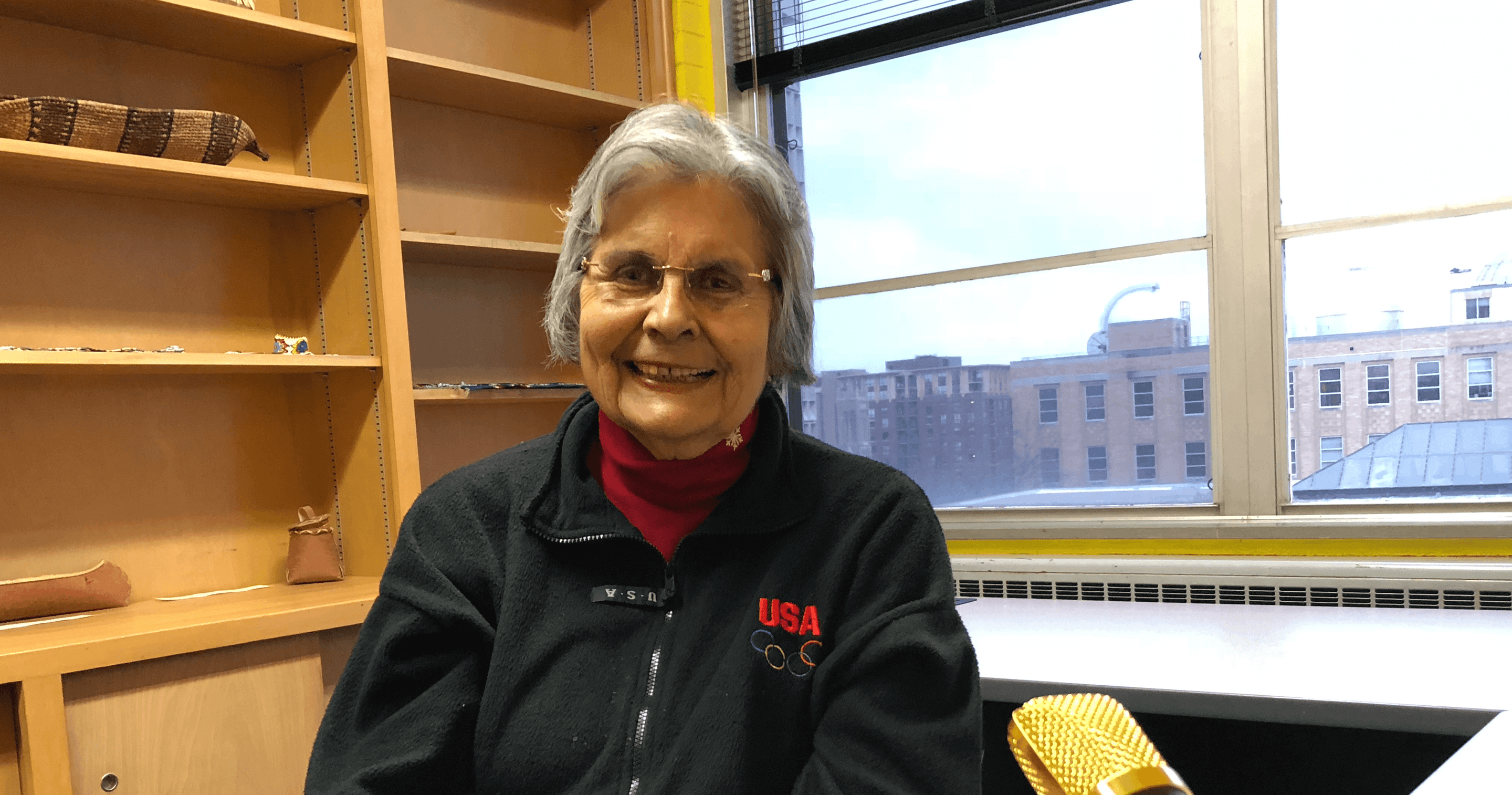

Ada Deer grew up on Wisconsin’s Menominee Indian Reservation in a log cabin with no running water or electricity. She attended UW–Madison on a tribal scholarship, becoming the first member of the Menominee tribe to earn a UW–Madison undergraduate degree. It was the first of many firsts. Next up: she became the first American Indian to earn a master’s degree from Columbia University’s School of Social Work.

Deer worked relentlessly on behalf of the Menominee in their struggle to restore their land and sovereignty. In the 1950s, the federal government initiated a termination policy that led to the creation of a corporate body to manage the Menominee tribe. Deer helped to organize a grassroots effort that convinced President Richard Nixon to sign a law restoring federal recognition in 1973. As a result, Deer became the first woman to chair the tribe in Wisconsin. She said later, “At Menominee, we collectively discovered the kind of determination that human beings only find in times of impending destruction. Against all odds, we invented a new policy — restoration.”

Deer returned to UW–Madison in 1977 as a lecturer in the American Indian Studies program and the School of Social Work, and in 1992, she became the first Native American woman to run for Congress in Wisconsin.

The following year, President Bill Clinton appointed her to serve as assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She was the first woman to do so. One of her most important works in this role was applying her powers to federally recognize 226 Native villages in Alaska, as well as helping to set policy for more than 550 federally recognized tribes.

From 2000 to 2007, Deer directed UW¬–Madison’s American Indian Studies program. In 2010, she was recognized by the National Association of Social Workers as a Social Work Pioneer for her work as an advocate and organizer on behalf of American Indians. She was the inaugural participant in the Culture Keepers/Elders-in-Residence Program, a UW–Madison initiative that hosts Native elders on campus for educational exchanges.

Deer credits her mother, also a fierce advocate for Native Americans, for her confidence and conviction. “I speak up. I speak out,” she says. “I want to do, and I want to be, and I want to help. And I’ve been able to do it.”