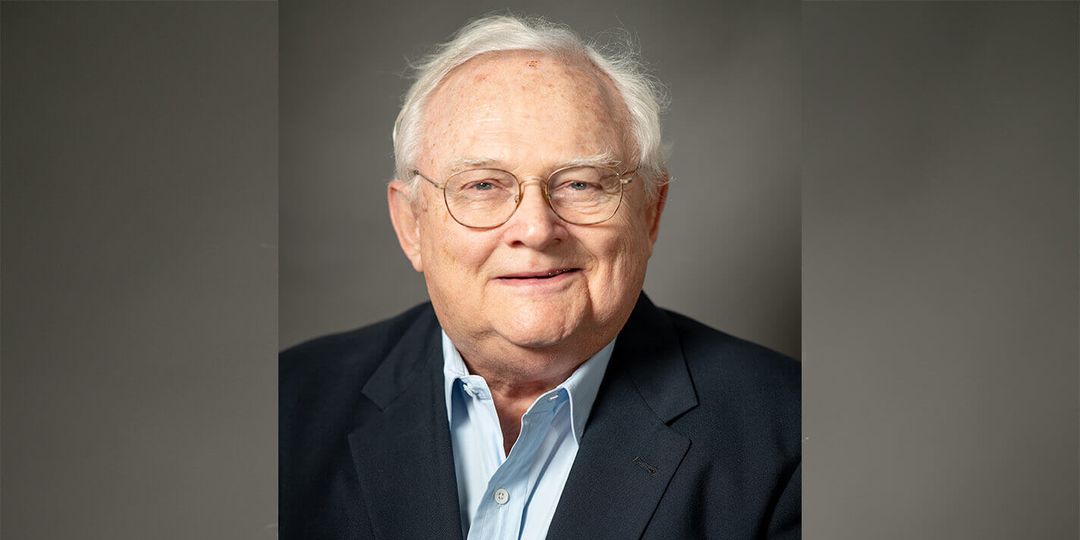

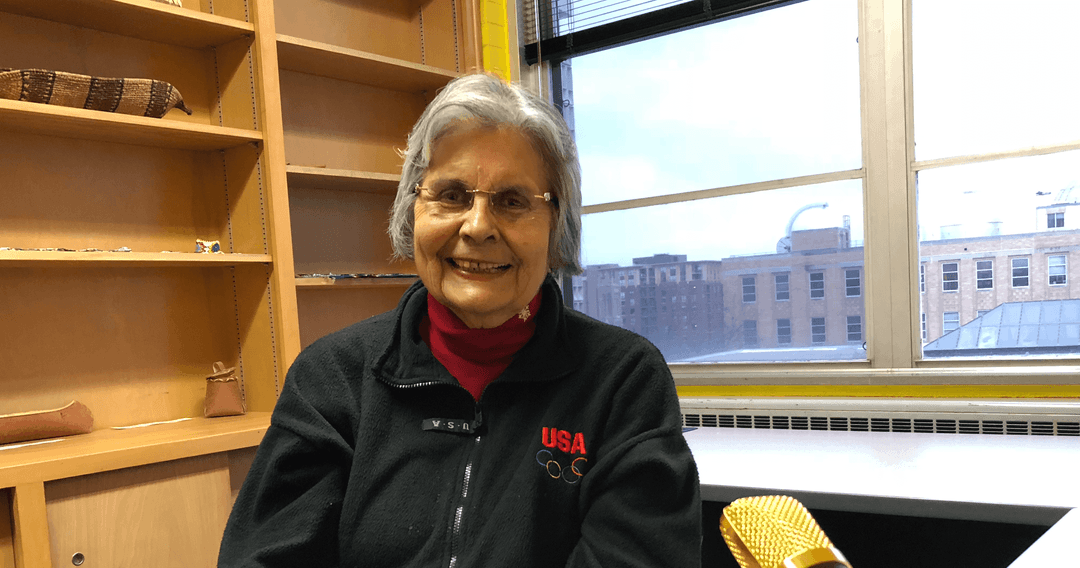

2012 Distinguished Alumni Award Honoree

Just the other week, Cora B. Marrett had a meeting in Washington, D.C.

Did she tell you it was at the White House? Did she tell you that President Barack Obama was there?

It’s unlikely. The soft-spoken scholar and higher education leader is known for her humility, wisdom, wit and patience. While she is grateful that the president nominated her for her current position as deputy director at the powerhouse National Science Foundation (NSF), she’s not terribly impressed with herself.

Others clearly are.

The 12th child of parents who barely finished the 6th grade in the small town of Kenbridge, Va., 70 miles from Richmond, Marrett earned a master’s and PhD in sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Last year, her undergraduate alma mater, the historically black Virginia Union University, awarded Marrett an honorary degree.

Colleagues call her a scholar and spokesperson for inclusion of all people, particularly those of African American descent and other underrepresented groups. Her rise to leadership at NSF, the major funder for many kinds of research in the United States, makes her story exceptional. The 1,700-employee agency awards some $7 billion annually, or 20 percent of all federal support for basic research in nonmedical fields of science, engineering, mathematics, computer science and the social sciences. She is known for raising the profile of the social sciences within the agency and for building bridges both within and beyond the NSF.

Marrett was a faculty member at UW-Madison from 1974 to 1997, with appointments in the departments of sociology and Afro-American Studies. She served as associate chair of the Department of Sociology from 1988–91 and was affiliated with the Energy Analysis and Policy Program and the Wisconsin Center for Education Research. During 1990–92, she held a half-time appointment while serving as director of two programs for the United Negro College Fund under a $2.4 million grant from the Andrew Mellon Foundation.

Marrett took a leave in 1976–77 as a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in California. Her first stint at the NSF was in 1992–96, when she served as assistant director and led the newly formed directorate for the social, behavioral and economic sciences.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, she also worked as an assistant professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina, an assistant/associate professor of sociology at Western Michigan University, and as a senior policy fellow at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C.

Wake Forest University awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1996. She was elected a fellow at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1998 and the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1996. She published widely in the field of sociology while serving in a host of public and professional service positions.

Then the big jobs began to roll in. In 1997, she took a top job in administration at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, the 23,000-student flagship of five campuses. In 2001, she was called back to Madison to become senior vice president for academic affairs for the University of Wisconsin System. In 2007, she was hired once again as an NSF assistant director, which led to the job of acting director in 2010 and finally deputy director in May 2011.

It all started back in the Kenbridge town library, where her mother would take Marrett and her sister to learn to read. They were the only African American people in the tobacco farming community to use the many books.

Her mother and father had a “love of learning,” she says, which surprises her now, because so many of their peers were illiterate.

Service to others also began early. In grade school, Marrett started “The Helpers,” a group of young friends who visited the sick and helped others in need in their small community.

Colleagues have recognized Marrett’s penchant for not just studying sociology, but also for doing something about the challenges she sees.

Marrett experienced segregation firsthand in Virginia, and her antidote was to get the best education she could. She headed to the historically black Virginia Union University for her undergraduate degree. Despite her family’s concern that she’d never get a job with training as a sociologist, Marrett set her sights on UW-Madison. She got there with a scholarship from the state of Virginia that encouraged African American students to leave the state to continue their education.

Colleagues commend Marrett for her behind-the-scenes efforts to help other people of color, such as her role in developing a Ford Foundation postdoctoral fellowship. The opportunity gives pre-doctoral students a year of mentorship so they can better navigate the choppy waters of academia.

In an award from the American Sociological Association in 2008, Marrett was cited for her work in “ensuring diversity.” She is credited with helping bring scholars and teachers of color to the field of sociology and nurturing them so they thrive.

For Marrett, her work in the past few years has focused not just on diversity of race but diversity of perspective.

“Our responsibility is to cultivate talent across all ethnic groups, genders, etc.,” she says of her roles at NSF.

She received the NSF’s Distinguished Service Award in the late 1990s for shaping the newly established social, behavioral and economic sciences unit, a nod to the agency’s effort to raise the profile of the social sciences in a time with much emphasis on natural science, technology, engineering and math.

The agency has not been without recent controversy. Last year, U.S. Sen. Tom Coburn, a conservative Republican from Oklahoma, issued a report claiming NSF was wasting money, particularly on social science research.

The controversy rallied the scientific community, with more than 100 scientific societies and institutions, including UW-Madison, signing a letter of support for NSF drafted by the American Association for the Advancement of Science in July 2011.

Despite controversies — or perhaps because of them — Marrett’s voice has been steady and strong.

Marrett became known for her ability to partner the natural sciences and engineering with the social sciences. And that reputation only grew with her continued leadership at NSF, where she was responsible for education and human resources.

“Sociology will gain a lot of visibility with a sociologist at the helm,” said Sally Hillman, the American Sociological Association’s executive officer when Marrett took on the new duties in 2007. Marrett’s charge was to concentrate on achieving “excellence in technology, engineering, and mathematics education at all levels and in all settings (both formal and informal) in order to support the development of a diverse and well-prepared workforce of scientists, technicians, engineers, mathematicians, and educators and a well-informed citizenry with access to the ideas and tools of science and engineering.”

Marrett emphasizes her mandate was to build bridges within the agency and to reach out to museums, universities and other institutions to assess and collaborate on NSF work.

She gained her latest accolades as an innovator and an outreach expert in this role. She gently but firmly advocates for her agency, and continues to make the case for the importance of listening to the general public.

“This is not a bureaucratic organization,” she said of the 1,700-employee agency. “It’s about people who have a commitment to excellence, and who want to help address the curiosity about the world around us.”

Marrett’s clarion call is to make sure that the interests of the general public are included in that effort and can help the agency focus on “what human beings are curious about anyway.” She summed up her enthusiasm for the agency’s mission in 2009 remarks to the NSF board: “The National Science Foundation is proud to participate in the fostering of discoveries and innovations of which the public dreams.”

Marrett is not sure where the next stop is, and Madison could be on the list. She still feels very close to former students and colleagues from whom she says she learns as much as she teaches. And her husband, Louis, lives in Madison, entailing frequent commutes to the city.

She is a member of the UW-Madison College of Letters & Science Board of Visitors. She and Louis established the Marrett Faculty Fellowship in Sociology, and provided a named fund to support the Chancellor’s Scholarship program.

“My life has never been terribly sequential and well planned,” she says. “I would never advise people to follow my path. I never know where something might come up.”

We’ll keep our eye on the White House.

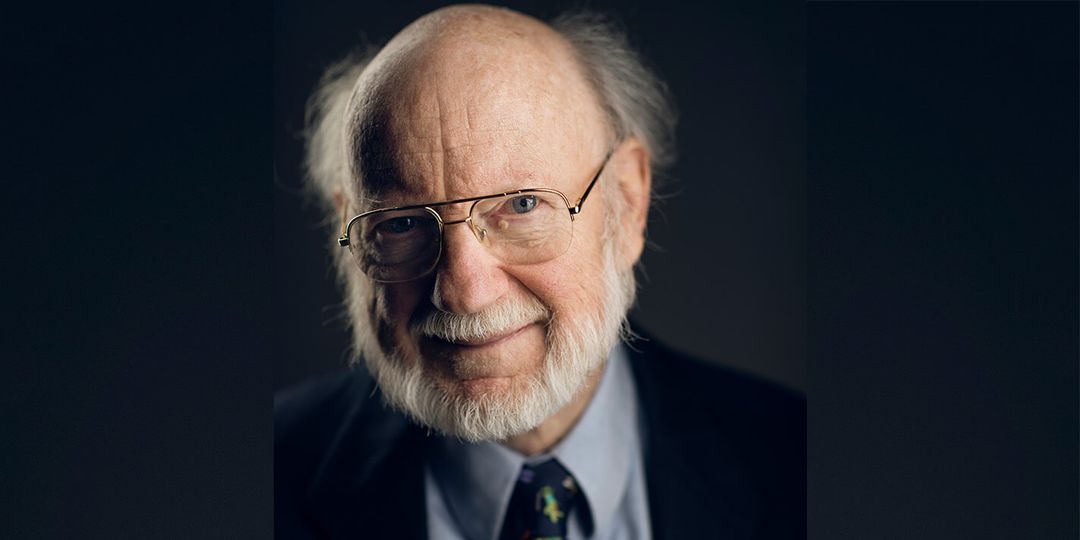

In Appreciation

“So you’ve never spent a winter in Wisconsin?” This question recurred in my conversations with residents of the Badger state when I arrived in 1963. Often the questioner expressed amazement that someone from Virginia could expect to survive the subzero temperatures of the upper Midwest. Interestingly, each subsequent description offered an increasingly bleak picture. “Well, you might survive,” a new acquaintance remarked in July. “After all, temperatures rarely stay below zero for very long.” “I should warn you,” another cautioned later, “that it’s not unusual for the thermometer to hover around minus 20 degrees for weeks at a time.” And one of the most distressing as summer transitioned to fall: “Go shopping now, for no store in Virginia could possibly have had clothing appropriate for a winter that averages minus 35 degrees beginning in October and continuing into April.”

I begin this brief saga with a commentary on climate, for time and again the limited diversity among students, faculty and staff at the University of Wisconsin is attributed to the harshness of the winters. Yet, the university has attracted and retained people from locales far more tropical than southside Virginia. The allure lies in the positive attributes of the university and in the experiences it affords. These are the features that attracted me to the University of Wisconsin and that account for my ongoing involvement.

That involvement started with a casual conversation I had with the chair of the sociology department at my undergraduate institution, Virginia Union University. When he learned of my interest in graduate study, he remarked: “You should consider the University of Wisconsin.” This remark came from Dr. H. J. McGuinn, well known at Virginia Union as a loyal supporter of Columbia University, his graduate institution.

I am grateful to Dr. McGuinn for his selflessness; I have never regretted following his advice. Granted, I applied to several institutions and chose the University of Wisconsin in no small part because it offered me a teaching assistantship. The institutional choice proved to be intellectually stimulating, with long-term consequences for my career.

Graduate education at Wisconsin provided me a strong grounding in the science of human endeavors. The courses and research experiences emphasized work that was systematic — rooted in and contributing to theoretical frameworks, built on methods that could be replicated, and yielding findings capable of being verified or falsified. This background prompts my contention that science lies in the approach to knowledge that is sought, not in the phenomena under investigation. Sociology, anthropology, psychology and other disciplines in the social and behavioral sciences share with geology, biology and chemistry a commitment to examining problems and processes through orderly techniques.

I gained my perspective on science from the courses I took and my years as a research assistant. I learned, more through observations than direct instruction, that one cannot develop expertise on everything. William H. Sewell, Joseph Elder, Michael Aiken — my faculty mentors and later my faculty colleagues — communicated the importance of knowing one’s own limitations and identifying experts to draw on. I do not claim that my fundamental curiosity — about the worlds we inhabit and create — emerged first at the University of Wisconsin. But I credit Wisconsin with fostering that curiosity and bolstering it.

In essence, the University of Wisconsin offered me a graduate school experience so energizing that the frigidity of the climate was never a factor in my decision to return to the university as a faculty member, as an administrator with the University of Wisconsin System, and now as a member of the board of visitors for the College of Letters and Science. I conclude that the Wisconsin climate mattered for me, but the elements of significance are not those linked to the wind chill index, the dampness of the air, or the depth of the ice on Lake Mendota. Rather, what counted: support for creative ideas, connections across intellectual and geographical boundaries, and dedication to the continued development of scholars at the cutting edge.